3. The chance to grow up safe and well

For the great majority of Australian children and young people, their families provide the factors and support needed for their health and well-being, including the necessary resources and experiences that enable them to grow and develop to become contributing members of their communities.

In circumstances where the child's immediate family may not be able to adequately provide for the positive development of their child, or require support themselves, extended family or other forms of Out of Home Care are required to step in and take on a supportive role in meeting these needs.

For these children and young people it is important that key objectives of the Out of Home Care system not only provide them with a safe environment but also ensure that they are able to achieve levels of health and well-being appropriate for their age.

The circumstances leading to Out of Home Care being required and the transition in to and out of care can have a significant impact on a child's or young person's health and well-being. Therefore, it is important to ensure that Out of Home Care service providers are equipped and supported to fulfil the role of parents, either temporarily or for the longer term.

Over the last 10 years, all Australian governments have increasingly recognised the importance of investing in the well-being of children and young people. Early childhood services, health, education, family support, cultural safety and child protection have become key focus areas to ensure children get the best start in life.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines 'health' as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.16(Opens external website)

WHO considers a state of well-being17(Opens external website) to be one where an individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.

The growing emphasis on children's well-being has led to continued improvements in data and information collection on the circumstances and experiences of children and young people. In Australia, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare18(Opens external website) and state government reports - including the Victorian Government's The State of Victoria's Children Report 200619(Opens external website) and the New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People National Consultation report20(Opens external website) - provide valuable information on the sector. Non-government organisations also produce reports such as the annual National Survey of Young Australians undertaken by Mission Australia21(Opens external website) and the CREATE Report Card 2009: Transitioning from Care: Tracking Progress.22(Opens external website) Together, these sources contribute valuable data and information on the experiences of children and young people, and insight into their views and aspirations.

A similar research focus is evident internationally. For example, The State of the Nation's Children published by the Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs in Ireland,23(Opens external website) The Good Childhood Inquiry: What Children Told Us, from The Children's Society24(Opens external website) in the United Kingdom, and The State of London's Children Report25(Opens external website) published by the Greater London Authority allow some inter-country comparisons to be drawn. It is also possible to assess changes in circumstances over time where studies are repeated, as is the case for the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports in Australia.26(Opens external website)

While the Australian and international research are not directly comparable, it is possible to identify several areas where a 'good' childhood experience is considered to be essential for a positive transition to adulthood.

3.1 Outcomes for children in Out of Home Care

It is widely reported that children who have been placed in Out of Home Care have poorer life outcomes than other children.27(Opens external website) Life outcomes are influenced by many factors, including the age that children enter care and the number of care placements they experience.

Although there is no national data available on the reasons children are placed in Out of Home Care, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has reported that children are placed in care because they are the subject of a child protection substantiation, because their parents are incapable of providing adequate care or because alternative accommodation is needed during times of family conflict.28(Opens external website) This indicates that children placed in Out of Home Care are likely to have experienced a significant life disruption and may require support to catch up on developmental stages.

Research has also shown that parental risk factors are often present in cases where children are placed in Out of Home Care.29(Opens external website) Of parents with children in care, 32 per cent had a psychiatric illness, 37 per cent reported alcohol abuse, 43 per cent reported substance abuse, and domestic violence was present in 56 per cent of cases.30(Opens external website)

Nowhere perhaps is the disadvantage experienced by children in Out of Home Care more apparent than in education. Research indicates that young people leaving care have poorer educational qualifications, are younger parents, are more likely to be homeless and have higher levels of unemployment, offending behaviour and mental health issues.31(Opens external website)

Research from Barnardo's in the United Kingdom found that:

- 70 per cent of young people in foster care and over 80 per cent in residential care leave school with no qualifications

- fewer than 20 per cent go onto higher education and fewer than 1 per cent to university

- children in residential and foster care are 10 times more likely to be excluded from school than their peers and up to 30 per cent are out of mainstream education

- between 50 and 80 per cent are unemployed between the ages of 16 and 25.32(Opens external website)

Similarly, research by the CREATE Foundation in 2006 indicated that young people in Out of Home Care do not perform as well as their peers at school and are more likely to have experienced disruption through relocation or exclusion.33(Opens external website)

The educational circumstances reported by participants indicated a number of key challenges faced by children and young people in care, including that they:

- are less likely to continue within mainstream education beyond the period of compulsion

- are more likely to be older than other children and young people in their grade level

- attend a larger number of primary and high schools than other students

- miss substantial periods of school through changes of placement.34(Opens external website)

Of the young people who responded to the CREATE 2009 Report Card on their current activities, almost a third (29 per cent) reported being unemployed or looking for work. A similar proportion reported being in full-time, part-time or casual work (28 per cent). A small number were studying at TAFE (11 per cent) and 2.8 per cent reported that they were at university.35(Opens external website)

CREATE has also collated information on the health outcomes of young people in care.36(Opens external website) Particular health challenges for these children include illness and disability, higher rates of teenage pregnancy, risk-taking behaviour and self-harm and poor access to dental, optical and aural health services. Mental health is also a significant issue for young people in care; research by the Royal Children's Hospital Mental Health Service shows that nearly two-thirds of children and young people in Out of Home Care had mental health diagnoses and required mental health referral.37(Opens external website)

Within child welfare literature, there is a growing interest in examining the positive experiences of those children and young people where residential or foster care has contributed towards better outcomes for them. In 2006, the Social Work Inspection Agency in Edinburgh identified the following five factors as critical to success:

- having people who care about you

- being given high expectations

- receiving encouragement and support

- being able to participate and achieve

- experiencing stability.38(Opens external website)

A recent Australian study also identified continuity of placement as an important factor in enhancing outcomes for children in care. The study found that young people 'who had had one placement that lasted for at least 75 per cent of their time in care were more positive about their time in care, were less mobile, and had better outcomes twelve months after they left care'.39(Opens external website)

Similarly, another current research interest is centred on improving and developing resilience within children and young people.40(Opens external website)

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, a key factor to success in Out of Home Care is a well-matched placement with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander family in line with the requirements of the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle.41(Opens external website)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people believe that a child's cultural and spiritual needs and their physical, emotional and developmental needs are of equal importance.

'Kids need to know their culture, otherwise all the things they have inside them don't mean anything.'42(Opens external website)

3.2 What do children and young people need to grow up safe and well?

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child affirms health and well-being as fundamental human rights - good health and well-being are crucial to effective participation in most aspects of life.

It is widely recognised that disruptions to a child's development can have an impact on long-term outcomes. For example, failing to transition effectively from preschool to primary school may impact on a child's future learning and educational attainment.43(Opens external website)

For many children and young people, transition points can be disrupted as they move into care, when they are in care and ultimately when they leave care.

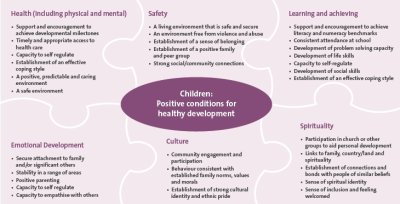

The following six areas have been identified as being the key areas of overall child well-being and providing a pathway for successful childhood transitions:

- physical and mental health

- safety

- culture and community

- spirituality

- emotional development

- learning and achieving.

Each area of well-being is influenced by a range of protective and risk factors. As indicated in Figure 1, there are a number of positive factors for healthy development in each area of well-being.

Figure 1: Positive conditions for healthy development of children and young people in Out of Home Care

The Out of Home Care system cannot provide all of the positive factors for child and youth well-being set out in the figure above. However, identifying what drivers of well-being Out of Home Care can influence, and defining what best practice is in those areas, is the primary focus of developing National Standards.

Each of the areas of child and youth well-being are discussed briefly below.

3.2.1 Physical and mental health

- Support and encouragement to participate in physical activity

- Nutrition and healthy eating

- Timely access to appropriate health services including: Dental, speech/ occupational therapy, counselling, family support

Critical developmental transition phases for children include the antenatal, birth, post natal periods, infancy, early childhood, primary school years, adolescent years, and the transition to adulthood. Within these phases, a variety of factors contribute to positive health and wellbeing outcomes.

Identifying and promoting a nurturing environment for the healthy development and growth of a child or young person continues to be a key focus for Australian governments.

The childhood and adolescent years are periods of significant growth, development and change, and the objective of all families is that their children live in environments that support optimal physical development.

Further, positive mental health is critically important for children and young people to develop emotional connections, stability and confidence. In research conducted in 2007, foster carers indicated that more than half (54 per cent) of children and young people living in foster care arrangements required professional help for their mental health issues; however, only 27 per cent received this assistance. Further, 61 per cent of children in foster care had exhibited behavioural problems compared with 14 per cent of those in the general community.44(Opens external website)

3.2.2 Safety

- An environment that is safe and secure

- An environment free from violence and abuse

- A space to call your own.

Feeling safe and secure is essential to emotional well-being and is generally understood to be a necessary precondition for good health.45(Opens external website) 'Safety' also includes cultural safety, a concept that acknowledges the need for 'an environment that is safe for people: where there is no assault, challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need'.46(Opens external website)

'Children's sense of security and safety increases when they have the protection of parents, a personal safe place to be, or trusted people around them.'47(Opens external website)

Safety encompasses a range of personal considerations, such as protection from the risk of personal injury and accident, protection from harm, exploitation or maltreatment, and protection from violence. This also extends to racism and the impact this has on all cultures, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people.

The stability and security of a child's environment also contributes to their sense of feeling safe. Stability in a child's life is important in ensuring that connections to family and the community are made and maintained, in particular for social and educational activities, and particularly as the outcomes for education are closely associated with stability.48(Opens external website)

Safety also involves external considerations, such as feelings of living in a safe neighbourhood and being free from the fear of crime. Both actual and perceived safety can have an impact on overall health and well-being. For example, there are associations between stress and anxiety in children and poor learning outcomes. Safety provides a key foundation for improved well-being and developmental outcomes.49(Opens external website) Parental perceptions of neighbourhood safety may also impact on a child's well-being, and lead to the child being restricted in their participation in outdoor activities, which may in turn lead to a sedentary lifestyle and the development of health issues associated with such a lifestyle.50(Opens external website)

3.2.3 Culture and community

- Spending time with family or friends

- Participation in cultural activities

- Access to community services relevant to your culture or identity

Most children and young people recognise that they belong to a community, and they commonly define this in terms of where they live. It is within this environment that children and young people seek to access many of the cultural, sporting and leisure activities that allow them to participate in a community that is broader than their family or school environment. This has particular resonance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as well as other culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including newly arrived migrants and refugees.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people, 'community' is defined in terms of a predominant connection to culture that is broader than the community within which they live,51(Opens external website) and this has been found to be the case wherever the child or young person lives.

The maintenance of connections to family, community and country forms the basis of the development of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child's identity as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person, their cultural connectedness, and the emergence of their spirituality.52(Opens external website) For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, strong cultural identity is integral to who they are and a source of pride. The teaching, maintenance and regaining of Aboriginal cultural practices for Aboriginal children are the responsibility of the whole community.53(Opens external website)

For young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, maintaining a sense of culture and links to the community are also important. As noted in research cited by the NSW Department of Communities, children placed within culturally/ethnically similar families, or families specially trained and assessed to provide culturally competent care, have the following benefits:54(Opens external website)

- better communication and less misinterpretation due to language and cultural barriers

- a positive sense of self and ethnic identity

- familiarity with food, language and customs

- increased stability of placement

- reduced need for caseworker intervention due to cultural and linguistic issues.

3.2.4 Spirituality

- Support and encouragement to participate in cultural and spiritual events

- Participation in church or community groups

The term 'spirituality' is open to a range of interpretations, and is often used to describe a person's inner life or to define those aspects of a person that are unseen, or intangible, but that give meaning or purpose to life. Spirituality is also used to describe a set of personal beliefs; it can be connected to a person's cultural or religious heritage, and may be linked to institutional religions or participation in church-based events and activities.

Spirituality can assist in ensuring that a child or young person develops a positive sense of identity and maintains connections with family and significant others enhancing their sense of belonging.

There is strong evidence that spirituality is important in shaping a young person's perception of their quality of life and, in this sense, it is understood to be important for health and well-being.55(Opens external website) Spirituality or connection to a church-based group as a strong protective factor for a child or young person is often cited in both Australian56(Opens external website) and international57(Opens external website) literature. Surveys of Australian youth provide evidence that spirituality, or faith, is important for 14 to 15 per cent of the young people surveyed.58(Opens external website)

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people, the development of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander spirituality is closely linked to family and country or land, and spiritual development depends on connections to particular people and places being maintained. Aboriginal spirituality has been described as feeling connections with people and places - feeling proud and knowing you have connections and bonds with people and being welcomed.

3.2.5 Emotional development

- Open and honest communication in your care environment

- Constant relationship with a trusted adult

- Maintaining or developing friendships with peers

Strong and positive relationships with family, friends and community are important for a child or young person's well-being, to their sense of self-worth and to the development of values or a moral code. Families play a principal role in teaching values, and significant adults in the family and broader social circle are key role models in this regard. Connections provide children with stability, without which emotional and psychological development can be adversely impacted. A focus on maintaining relationships ensures that children maintain stable contacts with significant people and groups and promotes better emotional and psychological development.

Some studies have shown an association between conditions such as depression and the presence of psychosomatic symptoms with poor child-parent relationships.59(Opens external website) Generally, the evidence confirms that friends, parents, relatives and family friends are the top three sources of advice and support for all age groups,60(Opens external website) that families are the main source for teaching values,61(Opens external website) and that family attachment is a strong, protective factor.62(Opens external website)

3.2.6 Learning and achieving

- Attainment of practical life skills including: self care skills, making friends and networks, basic cooking, basic budgeting, problem solving, learning to drive

- Consistent attendance at school

- Encouragement and access to resources to achieve literacy and numeracy benchmarks

Positive participation in education and learning is generally associated with strong lifelong outcomes. Such participation develops important cognitive skills, imparts knowledge and understanding that is important for a person's future, and provides an environment where children can develop important social and life skills.

The recent focus in Australian jurisdictions on the preschool and early primary years is supported by research demonstrating that participation in early childhood programs is beneficial for intellectual development and independence, sociability and concentration, and language and cognitive development. It is also associated with a lower incidence of personal and social problems in later life, such as school dropout, welfare dependency, unemployment and criminal behaviour. Participation and regular attendance at school, especially in the preschool and early primary years, is therefore of significant potential advantage to children from disadvantaged backgrounds.63(Opens external website) This focus must also extend to other key transition points, including Year 12 and further education or training, because most young people transition out of care between the ages of 16 and 18, while their peers stay at home into their twenties,64(Opens external website) with a potential impact on their ability to continue with education and training.

Available data and research indicates that areas of focus for assessing educational and learning experiences and outcomes include preschool participation rates, transition to primary school, achievement of specified benchmarks for literacy and numeracy, school attendance and retention rates, Year 12 completion rates, and successful transition to tertiary education, training and employment.

- http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html(Opens external website), accessed November 2009.

- http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/(Opens external website), accessed November 2009.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009), A Picture of Australia's Children 2009, Cat. No. PHE 112. Canberra: AIHW, is an example of such a report.

- V ictorian Government Department of Human Services (2006), The State of Victoria's Children Report 2006.

- New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People (2005), A National Consultation with Children and Young People on the Australian National Plan of Action for a World Fit for Children, NSW Commission for Children and Young People, Surry Hills, NSW.

- Mission Australia (2008), National Survey of Young Australians 2008: Key and Emerging Issues, Mission Australia, Sydney.

- McDowall, J (2009), CREATE Report Card 2009: Transitioning from Care: Tracking Progress, Sydney: CREATE Foundation.

- Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, Ireland (2008), State of the Nation's Children, Department of Health and Children, Dublin.

- The Children's Society, UK (2006), The Good Childhood Inquiry: What Children Told Us, The Children's Society, United Kingdom.

- Mayor of London (2004), The State of London's Children Report, Greater London Authority, London.

- Annual reports (e.g. Child Protection Australia) published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare enable comparisons over time.

- Bromfield, L., & Osborn, A. (2007), 'Getting the big picture': A Synopsis and Critique of Australian Out-Of-Home Care Research, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne, http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues26/issues26.html(Opens external website)- accessed December 2009.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2009, Child Protection Australia 2007-08, Child welfare series no.45 Cat. No. CWS 33. Canberra: AIHW, p. 52.

- Victorian Ombudsman (2009), Own Motion Investigation into the Department of Human Services Child Protection Program, Victorian Ombudsman, Melbourne,, p. 61.

- Victorian Ombudsman (2009), Own Motion Investigation into the Department of Human Services Child Protection Program, Victorian Ombudsman, Melbourne,, p. 61.

- Stein, M (2006), 'Research Review: Young People Leaving Care', Child and Family Social Work 2006, 11, 3, 273-9.

- Cited in Jackson, S & Sachdev, D (2001), Better Education, Better Futures: Research, Practice and the Views of Young People in Public Care, London: Barnardo's.

- Harvey, J & Testro, P, (2006), CREATE Education Report Card, p. 10 , Sydney, CREATE Foundation

- Harvey, J & Testro, P, (2006), CREATE Education Report Card, p. 10 , Sydney, CREATE Foundation

- McDowall, J, (2009), CREATE Report Card 2009. Transitioning from Care: Tracking Progress, Sydney: CREATE Foundation.

- Harvey, J & Testro, P, (2006), CREATE Health Report Card, Sydney, CREATE Foundation.

- N Milburn, Royal Children's Hospital Mental Health Service (2005), Protected and Respected: Addressing the Needs of the Child in Out of Home Care: The Stargate Early Intervention Program for Children and Young People in Out of Home Care, Royal Children's Hospital Mental Health Service.

- Happer, H, McCreadie, J & Aldgate, J (2006), Celebrating success: What helps looked-after children succeed, Edinburgh: Social Work Inspection Agency.

- Cashmore, JA, & Paxman, M (2006), 'Predicting after-care outcomes: The importance of 'felt' security', Child and Family Social Work, 11, 232-41.

- Gilligan, R (2000), 'Adversity, Resilience and Young People: the Protective Value of Positive School and Spare Time Experiences', Children & Society, Vol 14.

- Secretariat of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children (2005), Achieving Stable and Culturally Strong Out of Home Care Policy Paper, p.15.

- Secretariat of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children (2005), Achieving Stable and Culturally Strong Out of Home Care Policy Paper, p. 14.

- Ladd, JM and Price, JM (1987), 'Predicting children's social and school adjustment following the transition from preschool to kindergarten', Child Development, 58(5), 1168-89, Cited in Kay Margetts, Transition to School: Looking Forward, AECA National Conference, Darwin July 14-17, 1999; and Blair, 2001; Duncan et al., 2007; Reynolds and Bezruczko, 1993, Cited in The Smith Family and Australian Institute of Family Studies (2008), Home to School Transitions for Financially Disadvantaged Families, p. 2.

- Sawyer M, Carbone J, Searle, A and Robinson. P (2007), The mental health and well-being of children and adolescents in homebased foster care.

- Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2006), The State of Victoria's Children Report 2006, p. 76.

- http://culturalsafetytraining.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=…(Opens external website), accessed December 2009.

- New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People (2007), Ask the Children: Overview of Children's Understandings of Well-being, p. 4.

- Stein, M (2006), 'Research Review: Young People Leaving Care', Child and Family Social Work 2006, 11, 3, 273-9.

- Government of the United Kingdom(2007), Aiming High for Young People: A ten year strategy for positive activities, UK: HM Treasury , p. 7.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009), Child Protection Australia 2007-08, Child Welfare Series No. 45, Cat. No. CWS 33, Canberra: AIHW, p. 97.

- New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People (2007), Ask the Children: Overview of Children's Understandings of Well-being, NSW , p. 15.

- Secretariat of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children (2005), Achieving Stable and Culturally Strong Out-of-Home Care Policy Paper, SNAICC, Melbourne , p. 8.

- http://www.vacca.org/03_about_us/beleifs_values.html(Opens external website)- accessed December 2009.

- NSW State Government (2003), Children and Young People from Non-English Speaking Backgrounds in Out-Of-Home Care in NSW Research Report, Department of Community Services NSW , p. 3 - originally produced by the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, 2003.

- World Health Organization (1998), Health Promotion Glossary, WHO, Switzerland . http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/(Opens external website) about/HPR%20Glossary%201998.pdf,accessed November 2009.

- Commonwealth of Australia, Pathways to Prevention: Developmental and Early Intervention Approaches to Crime in Australia, op. cit., p. 38.

- World Health Organization (2005), Risk and Protective Factors, http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593652_(Opens external website) eng.pdf,accessed November 2009.

- Mission Australia (2008), National Survey of Young Australians 2008: Key and Emerging Issues, p. 9.

- Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, Ireland, p. 42.

- Mission Australia (2008), National Survey of Young Australians 2008: Key and Emerging Issues, p. 15.

- New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People (2007), Ask the Children: Overview of Children's Understandings of Well-being, p. 14.

- For example, Commonwealth of Australia (1999), Pathways to Prevention: Developmental and Early Intervention Approaches to Crime in Australia, April 1999, p. 72.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009), A Picture of Australia's Children 2009, Cat. No. PHE 112, Canberra: AIHW, p. 48.

- Stein, M, 'Research Review: Young People Leaving Care', Child and Family Social Work 2006, 11, 3, pp. 273-9.