PART C: Detailed Recommendations

A New Formula for Assessing Child Support

To address the issues identified in the earlier chapters of this Report, the Taskforce proposes a fundamental change to the formula used in the Child Support Scheme.

Overview of the proposed new formula

The essential feature of the proposed new scheme is that the costs of children are fi rst worked out based upon the parents’ combined income, with those costs then distributed between the mother and the father in accordance with their respective shares of that combined income and levels of contact.

The resident parent is expected to incur his or her share of the cost in the course of caring for the child. The non-resident parent pays his or her share in the form of child support. Both parents will have a component for their self support deducted from their income in working out their Child Support Income.

This gives practical expression to the first objective of the Scheme—that parents share in the cost of supporting their children according to their capacity. The proposed scheme is based upon the ‘income shares’ approach used in many other jurisdictions and reflects the notion of shared parental responsibility contained in Part VII of the Family Law Act 1975.

The proposed formula will be based upon Table A: Costs of Children, in this Report. The table expresses the cost of the child as a percentage of the parents’ combined income above their individual self-support amounts in two age groups, 0–12 and 13–17. These percentages are based as far as possible on the estimates of the net costs of children explained in the previous chapter. The costs represent the best estimate the Taskforce can make of the amount that parents on average spend on children in these age groups out of their own incomes.

In settling on the percentages that apply above the self-support amounts, the Taskforce took account of the present operation of the Maintenance Income Test (see Chapter 11).

Another theme of the recommendations in this chapter concerns the importance of having consistency in the approach towards separated families across different areas of government policy. A number of recommendations therefore concern the interface between child support, income support and family payments.

The recommendations in this chapter explain in detail how legislation should be drafted and the Scheme put into operation to give effect to the intentions of the Taskforce. For this reason, many of the recommendations are technical in nature.

Although the formula may be legislatively complex, it will be no more complex to administer than the current formula, nor will there be any greater complexity for the general public. At the present time, people can use a calculator on the Child Support Agency (CSA) website to obtain an estimate of a child support liability if they know the father’s income, the mother’s income, and the number of children. With the addition of the requirement to enter the ages of the children, it will be as simple for a member of the public to obtain an estimate of the new child support liability as it now is.

The income-shares approach

The income-shares method has been adopted by a majority of US states. It begins with a figure for the costs of the child based upon combined parental income, and then distributes that cost between the parents in accordance with their respective share of that combined income—in other words, their capacity to pay. The primary caregiver is assumed to meet her or his share of that cost in kind. The non-resident parent’s share becomes the child support obligation.

The major difference between the income-shares approach and the ‘percentage of obligor income’ approach that is now the basis for the Australian Scheme is the explicit inclusion of both parents’ incomes, in a way that parallels likely expenditure by those parents as if in an intact household where both parents have income. In American jurisdictions that use the income-shares approach, the percentage of income required for the calculation of both the cost of children and child support amount declines as combined parental income increases. Although the total combined child support contribution required of the parents increases with combined income, it does not rise proportionately to income.

But for this difference both approaches would yield the same child support requirement for the liable parent. The flat percentage liability, calculated only by reference to the liable parent’s income, will produce the same proportional share of the cost of the child as that parent’s income bears to the total income of the two parents combined.

In principle, the income-shares approach is to be preferred for the following reasons:

- If the purpose of the child support scheme is to ensure that ‘parents share in the cost of supporting their children, according to their capacity’ then the amount of child support payable ought to be referable to some measure of the costs of, or average expenditure on, raising children.

- If the scheme does not generally take into account the income of both parents then it cannot demonstrate that the parties are sharing equitably in the reasonable costs of raising children.

- The income-shares approach is more transparent. It makes clear how much is being contributed by the mother, the father and the community to the child’s support.

- It makes change of assessment processes clearer. If there is a reduction in the liability of one parent, then either the increased costs must be borne by the other parent, or taxpayers must pay more, or the child’s living standards must suffer.

For these reasons, the Taskforce considers that, in principle, the income-shares approach is more appropriate for Australia’s current circumstances, and more in line with community values, than the current system in which the great majority of all child support liabilities are based upon just the non-resident parent’s income.

Recommendation 1, which describes the detail of the proposed new child support formula, is divided into 31 subsections to emphasise that these recommendations constitute a package of interdependent recommendations to be taken together.

Recommendation 1

The existing formula for the assessment of child support should be replaced by a new formula based upon the principle of shared parental responsibility for the costs of children. The new basic formula should involve first working out the costs of children by reference to the combined incomes of the parents, and then distributing those costs in accordance with the parents’ respective capacities to meet those costs, taking into account their share of the care of the children.

The measurement of income

The income basis for the calculation of child support for the current Scheme is taxable income, but with various deductions and exempted amounts added back, and the gross value of the parent’s reportable fringe benefits included. Conceptually, this is similar to the definition of income for Family Tax Benefit (FTB) purposes, except that with FTB the calculation of some of the components is slightly different, and it includes many tax-free pensions or benefits.

The Taskforce considers that it is desirable not to multiply the definitions of income across government policy without a clear basis. It concluded that, in principle, the definition of income for the purposes of the Child Support Scheme should be no different from the definition for the purposes of government benefits paid to families, particularly FTB. It is a matter for the Government how best to align the two defi nitions. Aligning the definitions does not necessarily mean that the period of assessment of income for FTB and child support should also be aligned.

In particular, the Taskforce considers that while the Child Support Scheme is based on taxable income, with such adjustments as are included within the defi nition of supplementary income, the definition of income should include non-taxable forms of income support. An example is the Disability Support Pension. While many of those on this pension are not able to work at all, and therefore will have incomes below the self-support amount, it is possible for a person to do some paid work while on a disability pension. For that reason, it ought to be included in the definition of income for child support purposes.

FTB payments should not however be part of the income base of the parents. The Government’s contribution to the costs of children through FTB Part A has already been factored in to calculate the net cost of the child for distribution between the parents. It would be counted twice if additionally included as income in the hands of either parent. FTB Part B is more problematic. However, it provides additional support for sole parents and families with one main earner, compensating them in some cases for having access to only one tax-free threshold and for the opportunity costs for the parent with reduced work opportunities because of their care for children. The Taskforce considered such compensation should not be treated as available for the support of the children, and so FTB Part B should not be included as income for child support purposes.

Recommendation 1.1

For the purposes of the formula, the current definition of adjusted taxable income should be broadened to include certain non-taxable payments such as certain forms of income support, currently exempt.

Recommendation 1.2

The definitions of income for child support and Family Tax Benefit (FTB) should be consistent and the components should be the same.

The self-support amount

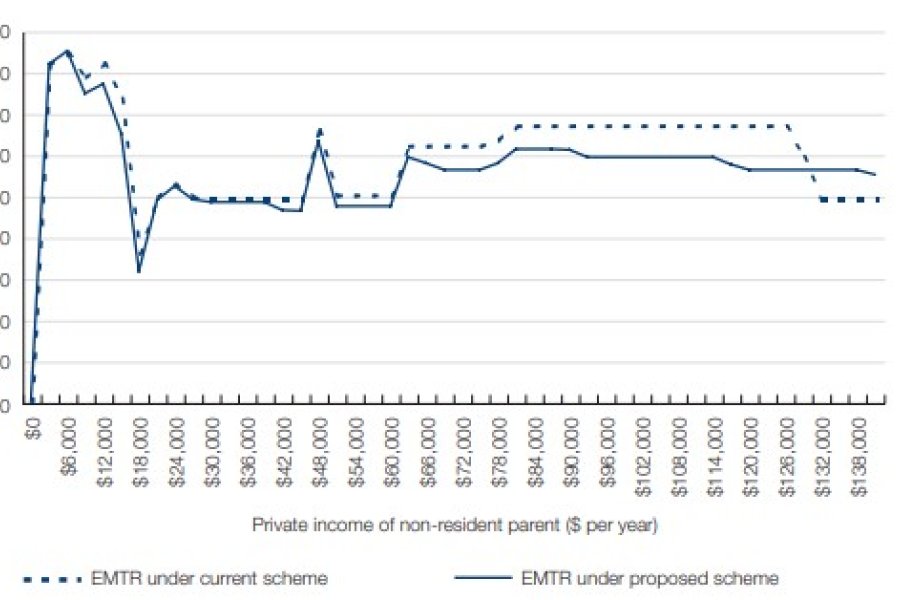

The basic self-support component (or exempt amount, as it is known) is an important feature of the existing Scheme, and the Taskforce recommends that it be increased. Concerns have long existed as to the adequacy of the current level of the exempt amount. This was one of the key issues raised with the Parliamentary Inquiry. One argument is that the current level creates serious work disincentives for some non-resident parents. The House of Representatives Committee concluded that the level of the self-support allowance should be raised.

In order to respond to the concerns about work disincentives, the Taskforce took into account the applicable taper rates for income support in setting the self-support component. In keeping with the linkage of other base values for the Scheme to average earnings, and adjustments with changes in such earnings, the Taskforce proposes that the self-support amount be set at one-third of Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (MTAWE).

The Taskforce also recommends that both parents should have the same self-support amount, since the income of the payee is treated differently in the proposed new scheme, and does not operate to reduce the Child Support Income of the payer. It is therefore unnecessary to include the resident parent’s contribution to support of the child by disregarding his or her income below average weekly earnings of all employees. Instead, the resident parent’s contribution by caring for the child is recognised expressly in the assessment of the parents’ respective child support obligations.

The Taskforce’s first approach was to treat the self-support amount as a ‘fl oor’ or minimum, where the relevant percentage is applied to all income, but the child support rate is reduced if this would otherwise result in the payer having income of an amount less than the ‘floor’ for his or her own support. However, this approach has the disadvantage that it creates disincentives to increase income just above the ‘fl oor’ as every dollar in increased income up to a certain level would go towards child support. Instead, the Taskforce decided to adopt the approach under the existing Scheme in which a percentage of income above the self-support amount becomes relevant for child support purposes. Each parent requires a reasonable level of income for their own support in their circumstances of separation, before they have the capacity to support their children for the purposes of the Child Support Scheme. Even once this income level is reached, the proportion of this income not required for the support of the child is available to the parent. If a parent’s taxable income does not exceed the self-support amount, it is deemed to be zero for the purposes of the formula.

Recommendation 1.3

Each parent should have a self-support amount set at the level equivalent to one-third of Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (MTAWE). Their adjusted taxable income less the self-support amount should be their income for child support purposes (the Child Support Income). Their Child Support Income should be zero if their adjusted taxable income does not exceed the self-support amount.

The Costs of Children Table

Two age bands

As indicated in Chapter 6, it is clear from all the available research evidence that expenditure on teenagers is significantly greater than that on preschool- and primary school-aged children.

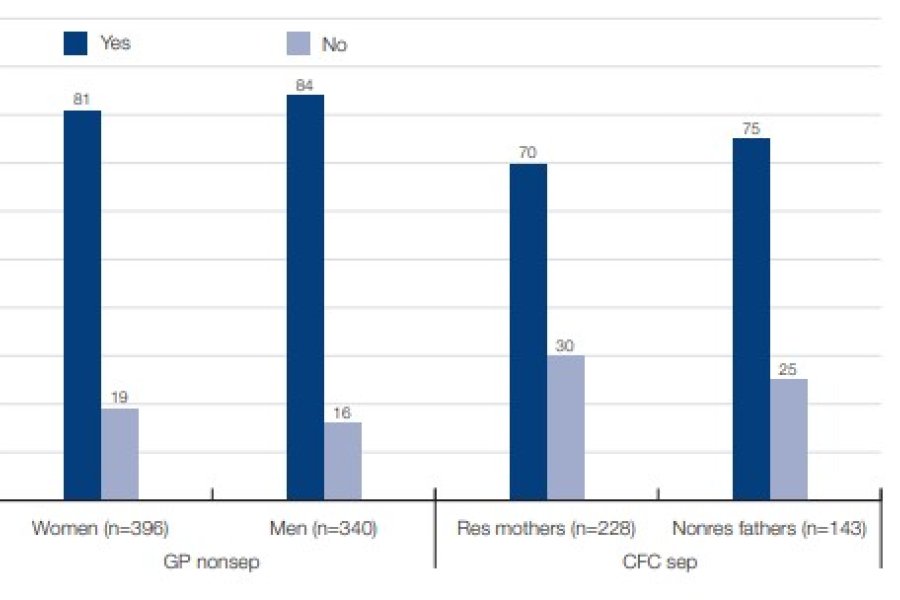

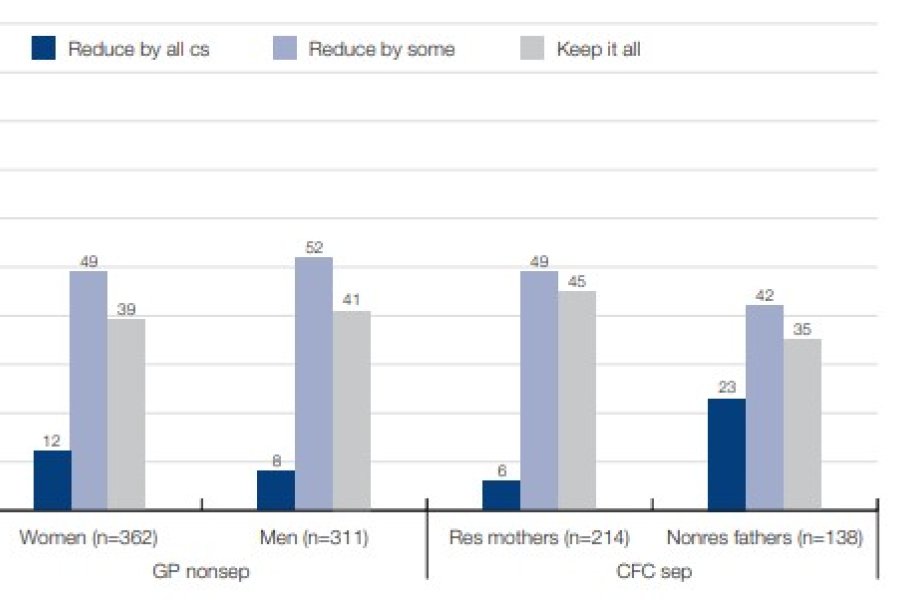

There is significant community support for the Child Support Scheme to refl ect this difference in the formula. Figure 9.1 shows the level of support for the idea that children’s ages should be taken into account in setting child support liabilities.

Figure 9.1: Do you think the amount of child support should depend on the children’s ages?

Notes: GP nonsep = general population non-separated sub-sample; CFC sep = Caring for Children after Parental Separation sample comprising separated/divorced parents with at least one child under 18; χ2 (3) = 17.91, p<.001.

Smyth B. & Weston R., ‘A snapshot of contemporary attitudes to child support’, in Volume 2 of this Report, p. 35.

In making estimates on the best available data of the costs of children, the Taskforce initially used four age groups. The findings for different ages of children in these categories are presented in Chapter 8. The Taskforce then considered that, for the purposes of the formula used in the Scheme, having four groups would be unnecessarily complex. It decided to align the age groups for the Scheme broadly with FTB Part A, by having two age groups, 0–12 and 13–17. (FTB Part A uses three age bands, with the amounts payable for 16 and 17 year olds being lower than for younger teenagers.)

Where there are children in different age bands in the one family, the costs of the children should be the average of the amounts applicable in each band. For this reason, Table A: Costs of Children also has a third set of percentages that apply to combinations of children between the age bands.

A Costs of Children Table not based upon fixed percentages of income

Table A: Costs of Children (in this chapter) provides percentages for each portion of income above the self-support threshold of each parent. In order to achieve automatic indexation, each threshold is expressed as a proportion of MTAWE above the self-support amounts.

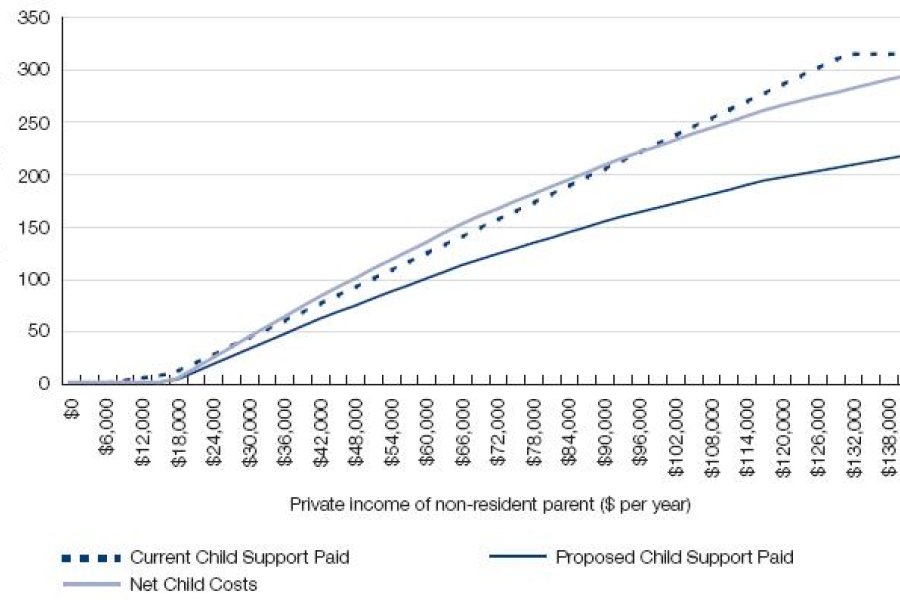

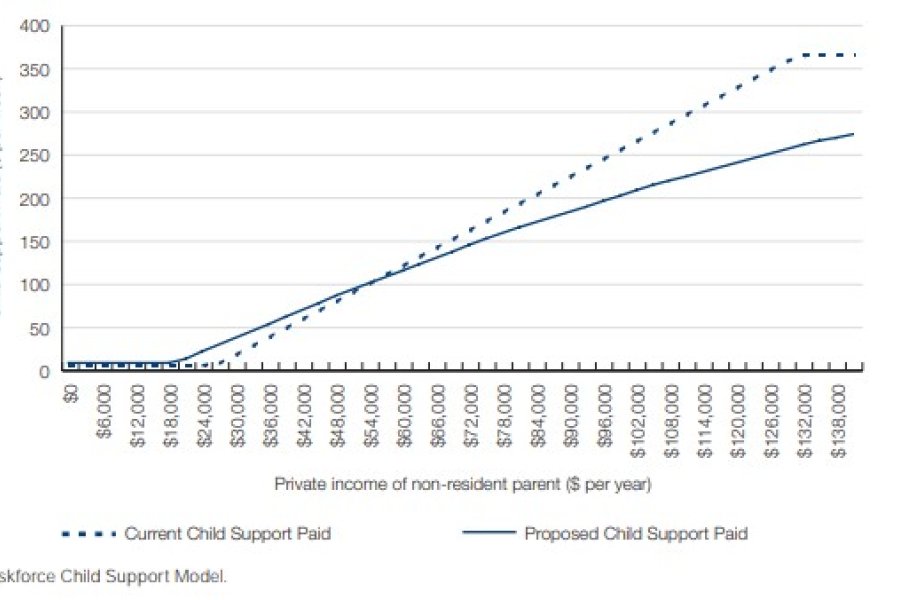

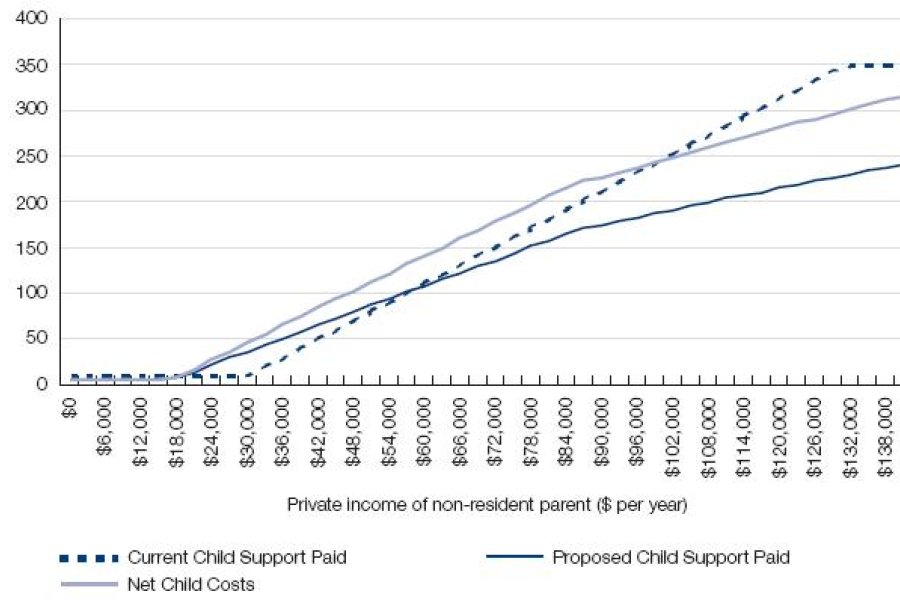

Since parents spend more on children the more money they have, but spend less as a percentage of their household income in the higher income ranges, the percentages applicable in this formula gradually decline as combined taxable income increases. The proposed percentages map as closely as possible the research evidence on the net costs of children explained in the previous chapter. The rate of decline is greater for one child than for two or three children because of the way FTB interacts with parents’ own expenditure on children.

The applicable percentages operate like the tax system, but in reverse. That is, the costs of children are greater as a percentage of the first portion of income above the self-support threshold than as a percentage of higher portions.

As a consequence, a liable parent with a high income will pay much more in child support than a parent on a low income, but less as a percentage of his or her taxable income above the self-support amount than the parent on a low income.

Similarly, where the resident parent is earning a sufficient amount that the combined Child Support Income of the parents takes them into a higher bracket, then her or his income will reduce the amount that the non-resident parent has to pay. It will do so in a much more graduated way than under the current formula, which reduces liabilities more rapidly than is justified by the research on the costs of children. Under the proposed formula, child support obligations will be based upon the relative difference between the parents’ respective incomes.

The costs of childcare

In order to take account of the costs of childcare or income forgone by being out of the workforce to care for young children, the costs of children aged 0–12 have been based upon the research evidence on the costs of 5–12 year-old children. As seen in the previous chapter, these costs are substantially higher than the costs of children aged 0–4 for middle-income families.

In practice, childcare costs can vary enormously depending on the location of the childcare and whether or not the care is being provided by a commercial provider. Where childcare costs are particularly high, as they are in some parts of the country, the parent incurring this cost will be able to apply for a change of assessment to help meet this cost. This is an existing ground for a change of assessment under the Scheme. Parents of young children should also be encouraged to discuss the issue of childcare costs when negotiating financial arrangements following separation through Family Relationship Centres or in other ways.

Number of children

The current Scheme has percentages of income for up to five children. As discussed in Chapter 8, the Taskforce found in its research that, because FTB Part A is payable on a per child basis without taking into account any economies of scale within the family, the net costs of four or more children are little different from the costs of three. For this reason, the Taskforce has concluded that it is only necessary to have a percentage of combined income for three or more children in the formula. Where there are more than three children, the age of the eldest three should be the measure of the cost of all the children.

However, for the purposes of calculations, it may be necessary to measure costs of individual children for some situations. These may include situations where a parent has different contact arrangements with different children, or where a change of assessment decision or other variation (such as an agreement) differentiates between the costs of individual children in the same family. As a result, there should be a system for allocating a cost to individual children where necessary, based upon the Taskforce percentages.

Recommendation 1.4

The costs of children for the purposes of calculating child support should refl ect the following:

- expenditure on children rises with age; and

- as income rises, expenditure on children rises in absolute terms, but declines in percentage terms.

Recommendation 1.5

The costs of children shall be expressed in a Costs of Children Table based upon the parents’ combined Child Support Income in two age bands, 0–12 and 13–17, and in combination between the age bands for up to three children. (See Table A: Costs of Children.)

Recommendation 1.6

Where there are more than three child support children, the cost of the children shall be the cost of three children, and where the children are in both age brackets the cost of children is based upon the ages of the three eldest children.

Recommendation 1.7

Where there is more than one child support child, and the arrangements concerning regular contact or shared care differ between the children, the cost of each individual child is the cost of the total number of children divided by the total number of such children.

| Parents’ combined Child Support Income (income above the self-support amounts)1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs of children (to be apportioned between the parents) | |||||||

| Children aged 0–12 years | |||||||

| Children aged 13+ years | |||||||

| Children of mixed age | |||||||

| Number of children | 0 – $25,324 2 | $25,325 – $50,648 3 | $50,649 – $75,972 4 | $75,973 – $101,296 5 | $101,297 – $126,620 6 | Over $126,620 6 | |

| 1 child | 17c for each $1 | $4,305 plus 15c for each $1 over $25,324 | $8,104 plus 12c for each $1 over $50,648 | $11,143 plus 10c for each $1 over $75,972 | $13,675 plus 7c for each $1 over $101,296 | $15,448 | |

| 2 children | 24c for each $1 | $6,078 plus 23c for each $1 over $25,324 | $11,902 plus 20c for each $1 over $50,648 | $16,967 plus 18c for each $1 over $75,972 | $21,525 plus 10c for each $1 over $101,296 | $24,058 | |

| 3+ children | 27c for each $1 | $6,837 plus 26c for each $1 over $25,324 | $13,422 plus 25c for each $1 over $50,648 | $19,753 plus 24c for each $1 over $75,972 | $25,830 plus 18c for each $1 over $101,296 | $30,389 | |

| 1 child | 23c for each $1 | $5,825 plus 22c for each $1 over $25,324 | $11,396 plus 12c for each $1 over $50,648 | $14,435 plus 10c for each $1 over $75,972 | $16,967 plus 9c for each $1 over $101,296 | $19,246 | |

| 2 children | 29c for each $1 | $7,344 plus 28c for each $1 over $25,324 | $14,435 plus 25c for each $1 over $50,648 | $20,766 plus 20c for each $1 over $75,972 | $25,830 plus 13c for each $1 over $101,296 | $29,123 | |

| 3+ children | 32c for each $1 | $8,104 plus 31c for each $1 over $25,324 | $15,954 plus 30c for each $1 over $50,648 | $23,551 plus 29c for each $1 over $75,972 | $30,895 plus 20c for each $1 over $101,296 | $35,960 | |

| 2 children | 26.5c for each $1 | $6,711 plus 25.5c for each $1 over $25,324 | $13,168 plus 22.5c for each $1 over $50,648 | $18,866 plus 19c for each $1 over $75,972 | $23,678 plus 11.5c for each $1 over $101,296 | $26,590 | |

| 3+ children | 29.5c for each $1 | $7,471 plus 28.5c for each $1 over $25,324 | $14,688 plus 27.5c for each $1 over $50,648 | $21,652 plus 26.5c for each $1 over $75,972 | $28,363 plus 19c for each $1 over $101,296 | $33,174 | |

- Calculated by adding the two parents’ Child Support Incomes, that is, adding each parent’s adjusted taxable income minus their self-support amount of $16,883 (1/3 of Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (MTAWE))

- 0.5 times MTAWE

- MTAWE

- 1.5 times MTAWE

- 2 times MTAWE

- 2.5 times MTAWE. Costs of children do not increase above this cap. Note that this equates to a cap at a combined adjusted taxable income of $160,386.

A cap on the costs of children

Expenditure on children becomes increasingly discretionary as household income increases. One couple may choose to make extra repayments on the mortgage, another may have regular overseas trips with the children, another may provide personal tuition for a child. The need to place a limit on the income to which the formula applies is recognised in the current Scheme by placing a cap on income at 2.5 times full time adult average weekly earnings for the purposes of applying the child support percentages. The cap for 2005 is $130,767.

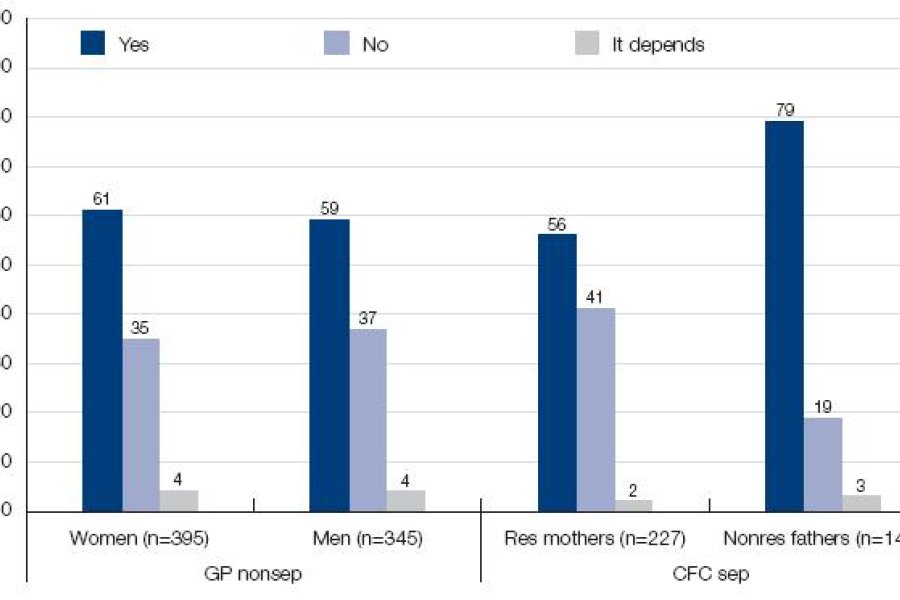

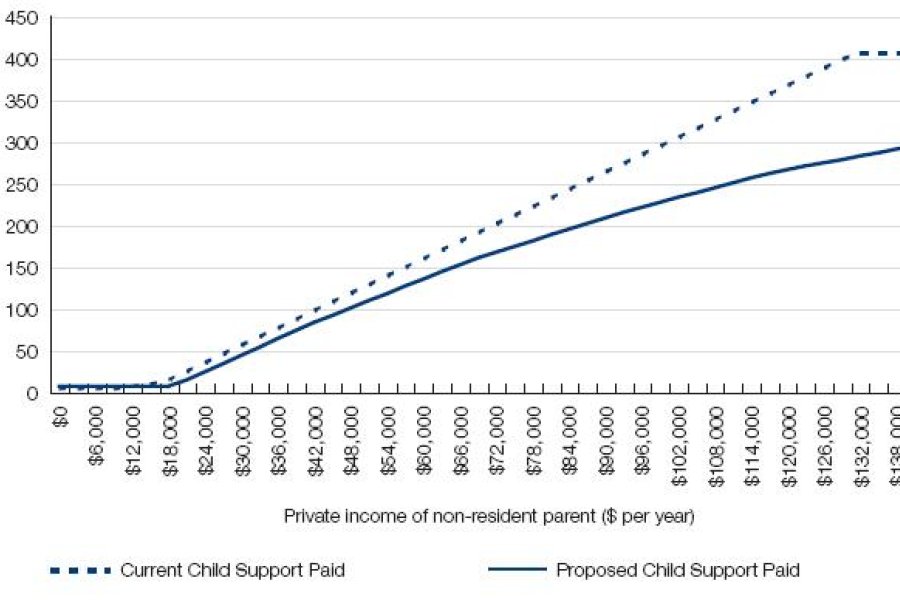

As shown in Figure 9.2, most respondents in the four groups in the attitudinal survey conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) supported the idea that there should be a cap on the amount of child support a high-earning non-resident father should pay.

Figure 9.2: Should there be a maximum amount of child support payable for high-income fathers?

Notes: GP nonsep = general population non-separated sub-sample; CFC sep = Caring for Children after Parental Separation sample comprising separated/divorced parents with at least one child under 18; χ2 (6) = 23.44, p<.01.

Smyth B. & Weston R., ‘A snapshot of contemporary attitudes to child support’, in Volume 2 of this Report, p. 34.

The Taskforce considers that it continues to be appropriate to limit the level of compulsory transfers under the Scheme. There is no obvious cut-off point for child-related expenditure. If a child is attending one of the most expensive private schools in Australia, the fees and additional costs for extra-curricular activities alone may exceed the total level of child support paid by liable parents whose income exceeds the cap under the existing formula.

However, nothing in the Child Support Scheme mandates that money transferred be used for a particular purpose. The formula is applicable whether or not parents choose to educate children privately, and whether or not they take expensive overseas holidays, or engage in any other such activities that involve child-related expenditure.

It follows that there must be mandatory limits on the level of transfers made, based on a generic formula. A parent may choose to pay more. It should also remain possible to exceed the cap through the change of assessment process. The Child Support Registrar already has a discretion to assess mandatory child support contributions in excess of the cap. At present, two reasons for a change of assessment are that:

- It costs extra to cover the children’s special needs.

- It costs extra to care for, educate or train the children in the way that the parents intended.

Only a small number of cases are likely to arise on this ground involving raising the cap.

Consistent with the income-shares approach, the Taskforce proposes that the cap will be on combined income for calculating the costs of the child, whether most of the income is in the hands of one parent or both have well-paid jobs. This would be expressed as a sum above each parent’s self-support amount, so it is a higher cap than now applies; under the present formula, the cap applies to income before the payer’s exempt amount is deducted. The Taskforce proposes that the costs of children be capped at a combined Child Support Income of 2.5 times MTAWE. This equates to a projected maximum combined income for 2005–06 of $160,386.

Recommendation 1.8

Combined parental Child Support Income for the purpose of assessing the costs of children shall not exceed 2.5 times MTAWE.

Determining a parent’s contribution to the costs of children

The formula should operate by first working out the financial needs of the child based upon the combined Child Support Incomes of the parents, that is, the proportion of the income of each of them that exceeds their self-support amount. That calculation would be based on Table A: Costs of Children. That cost is then shared in proportion to the parents’ respective Child Support Incomes.

Recommendation 1.9

The parents of the child or children should contribute to the relevant cost of the child or children in proportions equal to each parent’s proportion of the combined Child Support Income.

Regular contact and shared care

As noted in Chapter 6, one of the concerns about the current Scheme is that the formula is the same whether a non-resident parent is caring for the children for 29% of the nights per year or is not seeing them at all. This is difficult to justify. The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs, in its report Every Picture Tells a Story, proposed a number of reforms to the Family Law Act 1975 and a range of other measures to emphasise the desirability of shared parental responsibility and to encourage both parents’ involvement after separation to the maximum extent consistent with the best interests of the child. The Committee also recognised that there were some circumstances where shared parental responsibility was not in the best interests of children, in particular where there is a history of violence, child abuse or entrenched confl ict.

The Child Support Scheme and post-separation parenting

It is very important that the Child Support Scheme be aligned with government policy on post-separation parenting.

One aspect of this is that the Scheme ought to recognise the costs of regular contact in a way that is as fair as possible to both parents. The Terms of Reference of the Taskforce required it to provide advice on the recommendations of the House of Representatives Committee concerning changing the link between child support payments and the time children spend with each parent. The Taskforce was required to evaluate the existing formula percentages and associated exempt and disregarded incomes, having regard to data on the costs of children in separated households at different income levels, including the costs for both parents to maintain significant and meaningful contact with their children. It is clear therefore that the connection between the Scheme and the involvement of both parents in their children’s lives was central to the work the Taskforce was asked to undertake.

However, recognising the costs of contact in the Child Support Scheme is not at all straightforward. The Parliamentary Committee noted the findings of research that care of children in two separated households is significantly more expensive than care in an intact household. While a non-resident parent having regular contact with the children will necessarily spend money on the children while they are in that parent’s care, this expenditure may not greatly diminish the costs that the resident parent bears. The central issue is that many fixed costs, in particular housing, are duplicated. Furthermore, the greater the level of care by the non-resident parent, the more likely it is that there will be clothes, toys and other belongings in both households, to minimise the need for the child to carry everything in a suitcase from one house to the other.

Recognising regular contact in the formula

The Taskforce considers that when a parent has regular care of a child for at least one night a week, or an equivalent amount of time over the year during school holidays, this involves a parent incurring a level of expenditure that should be recognised in the formula. This level of care equates to care for 14% of nights per year, signifi cantly below the 30% of nights or more required for recognition under the current formula. Many of these costs are infrastructure costs, including appropriate accommodation and bedding. They do not vary much with the level of care involved. Others are consumption costs including expenditure on food, entertainment and transport.

Child support, FTB, and conflict about parenting arrangements

The Terms of Reference required the Taskforce to consider how the Child Support Scheme can play a role in encouraging couples to reach agreement about parenting arrangements. There may not be a great deal that the Scheme can do in a positive way to encourage parents to agree on parenting arrangements. The most useful sources of help will naturally come from the new Family Relationship Centres and other government initiatives to extend the services available for counselling and mediation. The CSA will no doubt be able to play a constructive role in supporting these initiatives (see Chapter 15).

There is, however, a way in which the Scheme could hinder parents from reaching agreement about parenting arrangements. One of the dangers of giving recognition to contact arrangements in the Scheme is that arguments about money can get in the way of reaching agreements that are in the best interests of the children. In the current Scheme, if the non-resident parent is caring for the children for at least 110 nights (30% of nights per year), this reduces his or her child support compared to the situation where the contact is for less than 110 nights. There is extensive anecdotal evidence that disputes between parents about contact arrangements have been motivated, at least in part, by the financial considerations arising if the number of nights of contact exceeds the 109-night threshold. The House of Representatives Committee heard evidence to this effect, and research on the Family Law Reform Act 1995 also reported anecdotal evidence of conflict around the 30% threshold for child support purposes. The desire to reduce child support can motivate a non-resident parent to want increased contact, or make the resident parent resist increased contact.

The potential for conflict is greatly exacerbated by the present arrangements for splitting FTB. Entitlement to FTB is based on the number of nights above 10% of the nights per year that each parent is caring for the child. Thus, arguments about whether the children will stay with the non-resident parent for two nights per weekend or three, or have time with him or her in the middle of the week, may have fi nancial implications.

Reducing conflict in the best interests of children

The Taskforce considers, on the basis of strong advice emerging from its consultations, that it is in the best interests of children that agreements about parenting arrangements not be affected by financial concerns. The Taskforce considers that the level of confl ict over money can be minimised if the recognised costs of contact in the formula do not vary between 14% and 34% of nights per year. Most non-resident parents who maintain an active involvement in their children’s lives will have a level of contact that exceeds the 14% threshold. Some will have daytime contact only, and this can also be recognised in the formula in some circumstances (see 9.76).

The Taskforce proposes that between 14% and 34% of care, the contact parent will be treated as incurring 24% of the total costs of the child while caring for the child. That means that the parent’s child support liability will be reduced by a fi gure representing 24% of the costs of the child. This is not only the mid-point between 14% and 34%. Evidence from the Budget Standards research (see Volume 2 of this Report) indicates that this reflects the findings of research on the proportions of the increased cost of children in two households that are incurred by each parent in separated families with a modest-but-adequate standard of living when regular contact is occurring.

Recommendation 1.10

Regular face-to-face contact or shared care by a parent should result in the parent providing the contact or care being taken to satisfy some part of their obligation to support the child.

Recommendation 1.11

If a non-resident parent has a child in their care overnight for 14% or more of the nights per year and less than 35% of the nights per year, he or she should be taken to be incurring 24% of the child’s total cost through that regular contact, and his or her child support liability should be reduced accordingly; but this should not result in any child support being paid by the resident parent to the non-resident parent.

Shared care

Where care is being shared between the two parents to the extent that each parent has the children for at least five nights per fortnight or 35% of nights per year, the applicable child support should be based upon a ‘shared care’ formula. For this group, it is proposed that the parent with the minority of the care should be treated as incurring 25% of the cost of the child at the 35% care level, rising to an equal sharing of costs at near equal provision of care, with every percentage point of care recognised in the assessment.

It is often the case that even where the care of a child is substantially shared, the parent with the care of the child the majority of the time incurs proportionately greater expenditure than the other parent on non-recurrent items, such as school uniforms and shoes. The Taskforce took the view that a tapered approach was better than treating the costs of the child as being provided pro rata by each parent.

The proportion of the costs of the child incurred by the parent with the fewer number of nights of care would be established by reference to Table B: Shared Care. The other parent incurs the remaining proportion of the costs of the child.

| Number of nights of care annually | Percentage of annual care | Proportion of net cost of child incurred |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 51 | 0 to less than 14% | Nil |

| 52 to 126 | 14% to less than 35% | 24% |

| 127 to 175 | 35% to less than 48% | 25% plus 0.5% for each night over 127 nights |

| 176 to 182 | 48% to 50% | 50% |

By this method, small changes in the levels of contact above the level for regular contact would not result in large changes in the child support arrangements. In other words, there is no cliff effect of crossing a threshold of a certain number of nights per year. Small changes would occur with increases in the level of care provided by the parent with the minority of nights. However, parents who are already in a shared care arrangement are more likely to have a cooperative approach to parenting and this reduces the risk that financial incentives will be a dominant motivation for making parenting arrangements.

In the proposed shared parenting formula, the costs that each parent incurs for the time the child is with him or her is treated as a ‘credit’ and deducted from the higher-income parent’s share of the cost of the child, resulting in that parent making a contribution to the lower-income parent. As at present, this may mean the parent with the care of the child for most of the time will make a contribution to support the child in the care of the other parent. By way of contrast, regular contact may reduce a non-resident parent’s child support obligation, but cannot result in payments from the resident parent to the non-resident parent.

Recommendation 1.12

Where the care provided by one parent is equivalent to 35% or more, the parent with 35% of the care of the child will be taken to be incurring 25% of the cost, rising to equal incurring of costs when the care of the child is shared equally. The way in which the costs incurred by the parent with the fewer number of nights of care per year is calculated is set out in Table B: Shared Care.

Daytime contact

Some parents do not have their children overnight often, and may not do so at all, but have extensive daytime contact. The costs incurred for such daytime contact can vary enormously. For a very young child, if visits occur in the primary caregiver’s home or the parent takes the child out in a pram or to a playground nearby, the costs involved in daytime contact may be quite small. Conversely, entertaining an older child for the day may incur substantial expenditure.

It is reasonable to give the same allowance for regular contact or shared care to parents with daytime contact, or a mixture of daytime and overnight contact falling short of the requisite level of nights, if a parent can establish that they incur a substantial level of expenditure on the child through daytime contact. The applicable test is whether the costs incurred are approximately equivalent to the costs the formula takes as incurred by having the care of the child for at least the minimum number of nights required for regular contact or shared care.

The CSA ought to encourage the parents to reach their own agreement about this, with assistance available from the Family Relationship Centres. The parents are best placed to know what expenditure on the child each typically incurs when the child is residing with them, including matters such as costs of transportation between the two homes, direct expenditure on meals and the costs of entertainment.

If the parents cannot agree, then the Child Support Registrar should be able to determine that the level of expenditure involved for a parent with daytime contact is suffi cient to justify treating the parent as having regular contact or shared care, as the case may be. If there are no infrastructure costs for housing as a consequence of having contact, then typically it would be expected that the daytime contact would need to be substantially in excess of 14% of the days in order to justify the Registrar determining that the parent is incurring costs equivalent to someone with regular contact of one night per week.

The onus will be on the parent seeking such recognition in the formula to make out the case to the Registrar. If the Registrar is not satisfied of that case, then no recognition of the contact will be provided in the formula. Like other discretionary decisions of the Registrar, this decision ought to be reviewable by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal or ultimately by a court.

Recommendation 1.13

A parent may also be treated as having regular contact or shared care if either the Child Support Registrar is satisfied, after consultation with the other parent, or the parents agree, that the parent bears a level of expenditure for the child through daytime contact or a combination of daytime and overnight contact that is equivalent to the cost of the child allowed in the formula for regular contact or shared care.

Splitting FTB

Consideration of the way in which regular contact and shared care are treated in the Child Support Scheme would be incomplete without considering how FTB is split, because each system treats post-separation parenting in a different way. Reforming one system cannot be effective without reforming the other and ensuring that the two systems represent a consistent and coherent policy.

When FTB was introduced, it became possible to split the benefit between parents as long as the non-resident parent had contact with the child at least 10% of the time. FTB Part A and Part B are both split in proportion to the share of the care of the child. Eligibility for FTB is based on each carer’s household income and individual circumstances.

Current arrangements for splitting FTB

Currently, separated parents entitled to FTB are able to share the payment for a child if they share the care of their child. The rate of FTB is apportioned between each parent in direct proportion to the caring arrangements in place. A parent must have at least 10% of the care of a child to receive FTB. In that case he or she would receive 10% of the FTB they would be entitled to on the basis of his or her new household income, while the other parent would receive 90% of the FTB they would be entitled to based on his or her new household income.

The level of care provided by each parent is assessed by using either the number of nights in care, or the hours of care for each FTB child. There may be some occasions where only counting the nights in care does not accurately reflect the caring arrangements for the child. In such cases, at the request of a carer, the actual number of hours of care may be calculated for each carer in determining the pattern of care and this is then converted into days in care.

The small incidence of FTB splitting

Only a small proportion of FTB customers share their payment. However, the proportion is increasing. In two years, the proportion of FTB shared care customers in the total FTB population has increased from 3.6% in March 2003 to 5.5% of the total population (around 100,000 FTB recipients) in March 2005. That is, about 50,000 parents split the FTB with the other parent.

Although the numbers of parents splitting FTB has increased over the years since the introduction of this option, the numbers remain modest when compared with the number of non-resident parents who have regular contact. Data derived from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey in 2001 indicated that 47% of fathers reported having children stay overnight, while a further 17% saw their children only during the day.

There are a number of reasons why eligible parents may have chosen not to split FTB. One is that the eligibility for that percentage share of FTB will depend on the circumstances of the non-resident parent. If that parent has a taxable income that is in excess of the amount giving an entitlement to maximum FTB Part A, while the resident parent does not, then less FTB Part A will be payable in the hands of the non-resident parent than the resident parent. Another reason why people may have chosen not to split FTB is that the non-resident parent does not want to deprive the resident parent of that income.

Problems with splitting FTB

There are a number of problems with the current arrangements for splitting FTB. First, the share of FTB is split in proportion to the amount of care that each parent has. While that may appear logical, the costs of children are not necessarily shared in proportion to the amount of time that is spent in each parent’s care. Where, for example, the children spend the great majority of the time with the resident parent, visiting the other parent every other weekend and for a portion of the school holidays, it is likely that the resident parent will still be purchasing the majority of the clothes and toys that the child needs and paying for school supplies and excursions. Other costs are duplicated in both households.

Secondly, the rules for splitting FTB and the rules concerning shared care under the Child Support Scheme are not aligned. Currently, the way in which contact and shared care arrangements affect entitlement to FTB is quite different from the position under the Child Support Scheme. Under the current child support formula, the child support obligation is not affected unless a parent has the child staying with him or her for 30% or more nights per year, or the parents agree that the parent should be treated as providing this amount of care of the child. In contrast, FTB can be split where a non-resident parent has 10% or more of the care. Although the care is normally based upon nights, it may be calculated by reference to hours of care. The FTB split is in direct proportion to the level of care, so that a parent with 20% of the time with the child will be eligible for 20% of both FTB Part A and Part B.

Thirdly, the FTB rules require processes for the resolution of disputes about the level of care provided in each household if the parents cannot agree, and this is an expense to Government that would be greatly reduced if FTB splitting were confined to shared care families. Currently, where the carers do not agree to the percentage of care, a Family Assistance Office decision-maker must determine the care percentage to be applied. This decision is based on the available evidence of what is the actual pattern of care. The carers are asked in writing to detail the level of care they provide. The shared care percentages are then determined on the information provided, even if only one carer responds. If only one carer provides evidence they are informed that the other carer may request a review of the decision.

Fourthly, the Reference Group and others with whom the Taskforce consulted indicated that the regime for splitting FTB based upon every 1% of care produces considerable conflict. It sometimes has the effect that efforts to reach agreement between the parents on the best arrangements for contact with the children are adversely affected by concerns about the financial repercussions of that decision in terms of entitlement to FTB.

Fifthly, the Taskforce is not persuaded by the policy rationale for splitting FTB Part B. In an intact family, FTB Part B is paid where one parent is not in the workforce or has only a low income from paid employment. Where parents are separated, its history suggests it has a different rationale. Single parent households are entitled to claim FTB Part B to compensate them for the loss of having two tax-free thresholds in comparison to intact couples with children. It is not at all clear why this benefit should be split merely because the child has contact with the other parent at least 10% of the time.

Offsetting FTB against child support for families with regular contact

In the proposed new methodology for calculating an appropriate level of child support, it is proposed that FTB Part A entitlements should be broadly considered as offset against child support obligations for families with regular contact, and that FTB splitting should be confined to those with shared care arrangements (35%+ nights each).

The non-resident parent’s child support should be calculated taking into account that the resident parent usually has a significant contribution from the Government towards the cost of children through FTB Part A. If the FTB were split between the parents where contact occurs for 10% of the time or more, then the non-resident parent who receives a share of the FTB Part A would also have to pay more child support because less would be in the hands of the other parent. It follows that they cancel one another out.

The Taskforce proposes that the child support and FTB systems be aligned, so that, rather than having two different systems for taking into account regular contact and shared care, there is one consistent approach. Recognition of the costs of regular contact should be dealt with through the Child Support Scheme rather than through FTB splitting, and the level of child support payable should be calculated on the assumption that the resident parent has the benefit of all the FTB Part A where the care is not being shared.

As a result of this reform, the scope for conflict over money, either in relation to child support or FTB, will be minimised; resident parents will have the guaranteed on-time payment of all of the FTB, and non-resident parents will have their child support obligations reduced significantly on account of the costs incurred in regular contact.

Recommendation 1.14

FTB Parts A and B should no longer be split where the non-resident parent is providing care for the child for less than 35% of the nights per year. Where each parent has the child in their care for 35% of the time or more, FTB should be split in accordance with the same methodology as in Table B.

Benefits for low-income parents with regular contact

The Taskforce was mindful of possible disadvantage that this change may produce for low-income non-resident parents, for whom the amount of child support paid is small by comparison with the level of FTB to which they may be entitled. The Taskforce noted that while the child support payer may not get a substantial fi nancial benefit from his or her share of the FTB, the value of the additional benefits flowing from FTB entitlement for low-income parents may be considerable. Such benefits include Rent Assistance, Health Care Card and other Medicare benefits. The Taskforce proposes that for this group who would otherwise be entitled to a share of FTB if the current system were continued, access to such benefits should be maintained.

Income support payments often include a ‘with child’ rate, where the recipient does not qualify for parenting payment but has care of a child to a specified level. Historically, parents were required to have care of 30% of nights annually. There has been some uncertainty about this rate since the introduction of FTB with its qualifying threshold of 10% care, however. Currently, the award of the ‘with child’ rate of Newstart Allowance does not appear to be administered uniformly. The Taskforce proposes that parents with regular contact (14% or more) be given the ‘with child’ rate, to ensure consistency across the country and to align Newstart Allowance with the recognition of regular contact under the Child Support Scheme. The research on the cost of children conducted by the Taskforce could be used to assess the adequacy of this allowance.

Recommendation 1.15

Non-resident parents who have care of a child between 14% and 34% of nights per year should continue to have access to Rent Assistance, the Health Care Card, and the Medicare Safety Net if they meet the other eligibility criteria for FTB Part A at the required rate. They should also be paid the ‘with child’ rate for the relevant income support payments, where they meet the relevant eligibility criteria. The Government should also consider the adequacy of the current level of this rate in the light of the research on the costs of children conducted by the Taskforce.

Determining the parenting arrangements

Currently, the CSA is required to make an administrative finding as to the level of care being provided by a parent in order to make a child support assessment. Where parents are in agreement that a particular level of care on the part of each is occurring, an assessment may be made on the basis of the agreed arrangements. However, in some cases the CSA may be placed in a position of having to determine care levels where there is parental dispute as to the level of care actually provided and anticipated to be provided into the future.

Where parents are in dispute, Family Relationship Centres will be available to assist them to negotiate parenting arrangements for the children, including the time children will spend with each parent. Family Relationship Centres will also have a role to help where such arrangements break down, or require renegotiation. The ultimate arbiter of disputes as to care arrangements remains courts with family law jurisdiction. Hence, parents with an agreed arrangement will have a parenting agreement setting out their mutual understanding. Where parents have had their dispute resolved in a court, the resulting court order will set out care arrangements.

It is problematic for an administrative agency to be required to make a ‘finding’ as to the specific joint care arrangements proposed into the future when the parents themselves do not agree about the arrangements occurring. The terms of a parenting agreement or court order may reliably form the basis for child support assessment on the basis of regular contact or shared care. Under the proposed scheme, if the parents are not in agreement, it will be up to the parent who wants the child support assessment to be calculated on the basis of a different level of care to seek to resolve the dispute about care arrangements with the other parent by seeking a variation to the parenting plan or court orders.

This will have the additional advantage of promoting certainty in parents’ child support arrangements where a parenting dispute has been resolved, and the agreed or court-ordered arrangements set out.

Recommendation 1.16

Child support assessment based upon regular contact or shared care should apply if either the terms of a written parenting plan or court order filed with the Child Support Agency specify that the non-resident parent should have the requisite level of care of the child, or the parents agree about the level of contact or shared care occurring.

However, there needs to be an exception to the general rule of no change, and in particular, no retrospective change. This relates to a complaint of some resident parents in cases where they have received reduced support on the basis of proposed regular contact, and such contact has not been denied, but the non-resident parent has failed to avail themselves of opportunities to see and care for their child.

In this exceptional circumstance, the resident parent should be able to seek a retrospective adjustment to the level of child support assessed. If there was a dispute about whether regular contact had been occurring, or whether the resident parent was to blame when contact did not occur, the matter would probably need to be resolved by a court. It would only be appropriate to justify a change in the child support assessment if there was a clear pattern established of failing to turn up for scheduled contact visits.

Recommendation 1.17

The resident parent may object to an assessment based upon the payer having regular contact if the level of actual contact usually occurring in the current child support period is significantly less than 14% care of the child or children, although the payee is willing to make the child or children available for that contact.

The general rules about adjustments during a child support period not being retrospective should continue to apply. There are often variations between the levels of contact that ought to occur and the levels of contact in practice as a result of everyday events, such as illness. These do not actually constitute a change to the general pattern of care and should not result in requests for variations to the assessment.

It is proposed that there should be a threshold level of change, below which no adjustment is made to the assessment until the next child support period, even where the change in care level would otherwise result in a change to the assessment. Where there has been a change in the care arrangements amounting to a regular change for the future of at least one night per fortnight (or approximately 26 nights a year), then it ought to be possible to ask the CSA for a new assessment based on the new care arrangements. The fact that there had been variations in contact arrangements, such as additional unplanned visits or missed visits due to unforeseen factors, would not suffice to justify a new assessment, as this would not be a change to the regular care arrangements for the future.

Recommendation 1.18

A new assessment may be issued during a child support period if the parents agree that there has been a change in the regular care arrangements amounting to the equivalent of at least one night every fortnight, or there has been a similar degree of change as a result of a court order.

Variations on the basic formula

The basic formula deals with situations in which the parents, although now separated, continue to support their children. However, families’ situations do not remain static. Either parent may re-partner and have a new family, they may then again separate with additional children to support, or children may be cared for by carers other than their parents. The new formula (in common with the current formula) must adequately handle each of these situations.

Second families

Tensions regularly arise when separated parents have re-partnered, and have a new family with the new partner. The parent feels the conflicting pressures of having children in two families to support, and the children will feel any differences in treatment between the parent’s new family and the old. The Child Support Scheme can only deal with these conflicting pressures on the basis of principle. As discussed in Chapter 7, the fundamental principle adopted by the Taskforce is that adopted by other Inquiries—that all children of a parent should be treated as equally as possible, irrespective of the order of their birth.

The current Scheme recognises a parent’s responsibility to new children for whom he or she has a legal duty of support. It does so by increasing the exempt amount of the parent by a substantial flat sum, plus amounts for each new child. However, the increase bears no relationship to the amount of child support paid for children in the parent’s previous family. The increase substantially overstates the costs of children in low-income families, but is inadequate to cover children’s costs at higher incomes. When new children arrive in an intact household, the income of their parent must be spread further, and the standard of living of all the children falls to some extent. If continuity of expenditure principles grounding the child support formula are extended, the available income of the parent to expend on the child support child should be reduced when new children arrive.

In order to demonstrate that children are being treated as equally as possible, the reduction should relate to the cost of the new children. This cost could be assessed to a large extent upon the principles outlined in the cost of children findings of the Taskforce. However, it must be assumed that the responsibility of the parent to their new children is undertaken alone, disregarding any income of a new partner of the parent. Cost calculated on this basis is a reasonable approximation of at least one parent’s share of the total cost of those new children, even where their new partner has income. It avoids involving a new unrelated person’s income in the child support calculation, with the administrative complexity this entails.

Because the new calculation under the proposed scheme considers only the new children, it assumes that there are no economies of scale in supporting those new children as well as the child support children. This reflects reality where it is the non-resident parent who has new children, although perhaps over-estimates the child’s cost where it is the resident parent who has new children to support, in addition to the child support children already in her or his care. The approach, however, may similarly be justified because it openly endeavours to treat the resident and non-resident parents of the child support child equally, while again avoiding too great a level of administrative complexity.

The calculated cost of the children in the new family would be deducted from the available income of the parent. The child support calculation for both the costs and allocation of the child support children may then occur as usual, although using that parent’s reduced income. The outcome will not produce mathematically identical amounts allocated to the support of children in the new and old family, but certainly demonstrates continuity in the principle behind the approach, which is clearly not achieved by the current formula.

While some parents with second families may receive a reduced allowance for the new child or children on the basis of this principle compared to the present provisions, the effect of this recommendation needs to be considered together with the impact of all the other recommendations, including a greatly increased self-support amount, fairer recognition of the costs incurred in contact, recognition that the same percentages of before-tax income should not be applied across the income range, a greater range of individual variations, and other changes to the way in which child support obligations are calculated. The availability of FTB to the second family should also be taken into account.

Recommendation 1.19

All biological and adoptive children of either parent should be treated as equally as possible. Where a parent has a new biological or adopted child living with him or her, other than the child support child or children, the following calculations should take place:

- establish the amount of child support the parent would need to pay for the new dependent child if the child were living elsewhere, using that parent’s Child Support Income alone;

- subtract that amount from the parent’s Child Support Income; and

- calculate and allocate the cost of the child support child or children in accordance with the standard formula, using the parent’s reduced income.

Split care

Another possible family arrangement in families with several children is where one parent takes responsibility for some of the children, and the other parent takes responsibility for the others. In these cases, it is not clear which parent will have the overall child support liability, as each is both a resident and non-resident parent (although to different children). Each may be assessed separately as liable for children in the care of the other parent. The liabilities of each parent may then be offset in order to find the overall payer parent. This is precisely what happens under the current formula.

Recommendation 1.20

Where parents each care for one or more of their children, each parent is assessed separately as liable to the other, and the liabilities offset.

Payments to children in more than one household

The situation of a non-resident parent supporting children to different resident parents fits uncomfortably with income-shares principles. Theoretically, an approach of treating each resident parent separately, and calculating the liability to each such parent using the standard formula would accurately reflect the costs of two separate households. However, the non-resident parent would never factually live in two separate households and support them each to a level as though the other household did not exist. The liabilities in this case should reasonably be limited by the capacity of the liable parent to provide support for the children as though they all lived in one household with the resulting economies of scale. As a result, it is necessary to disregard the income of the carer parents in this circumstance, and calculate the liability on the payer’s income alone. The non-resident parent will not then see any reduction in his or her obligation as the income of either payee parent rises.

However, the payers have already benefited from both households being treated as having the economies of scale of one household. Given this assumption, additional reductions for payee income would significantly underestimate the children’s needs. For this reason it is valid to disregard such income.

Recommendation 1.21

Where a non-resident parent has child support children with more than one partner, his or her child support liability should be calculated on his or her income only and distributed equally between the children.

Payments from more than one non-resident parent

In contrast with the situation of a resident parent who cares for children with different non-resident parents, the issues are slightly different when there is more than one non-resident parent. The resident parent in that instance has available economies of scale in caring for more than one child in the same household. However, each non-resident parent, unless they have contact with the children, may not necessarily know about the existence of the other child, nor of the details of the other child’s non-resident parent.

In theory an assessment could be performed based upon the costs of the children in combination, using the income of the minimum of three parents in combination, with adjustments for new families as per the standard formula. However, this is highly artificial, because it would be extremely rare for an intact household with these parameters to exist. There is little basis upon which the Child Support Scheme can justify performing an assessment involving the income and living arrangements of all three involved parties, with the breaches of privacy this involves. It would also be treating each non-resident parent as partially responsible for the support of the other child or children, to whom they are not biologically related, which seems unjustifi able.

On balance, the Taskforce feels that the treatment of such situations by the current Scheme should be retained, and the calculation and allocation of the cost of the children of each non-resident parent performed separately.

Recommendation 1.22

Where a resident parent cares for a number of children with different non-resident parents, each of the child support liabilities of the non-resident parents should be calculated separately, without regard to the existence of the other child or children.

Payments by the parents to other carers

A final variation that may be encountered is where neither parent cares for the child. Sometimes grandparents or other relatives will take over the primary care of the child, because neither parent is able to do so. This may be an informal arrangement, with the consent or acquiescence of the parents, or a formal arrangement either by court order or through child protection authorities placing the child with the relatives. Child support is payable by both biological parents in these circumstances.

Where the care by a person who is not the child’s parent is such that child support should be available, the fact that the person has no parental obligation to the child should be clearly recognised in the formula. His or her income should not be taken into account in any way by the calculation, which should be based upon the incomes of both parents of the child. This should not prevent recognition that a parent is incurring costs in providing some care of the child through regular contact or shared care, as recognised by the general formula.

Recommendation 1.23

Where a child is cared for by a person who is not the child’s parent, the combined Child Support Income of the parents should be used to assess their liabilities according to their respective capacities. Where a parent has regular contact or shared care of the child, that parent’s liability will be reduced in accordance with the normal operation of the formula.

Minimum and fixed payments

9.11.1 The $260 per year minimum

Since 1 July 1999, there has been a minimum payment of $260 per annum ($5 per week), even if the payer has an income below the exempt amount. The minimum payment of $260 was first proposed in 1994. The payment was not linked to any index when it was introduced, with the consequence that inflation since 1999 has eroded the value of the payment.

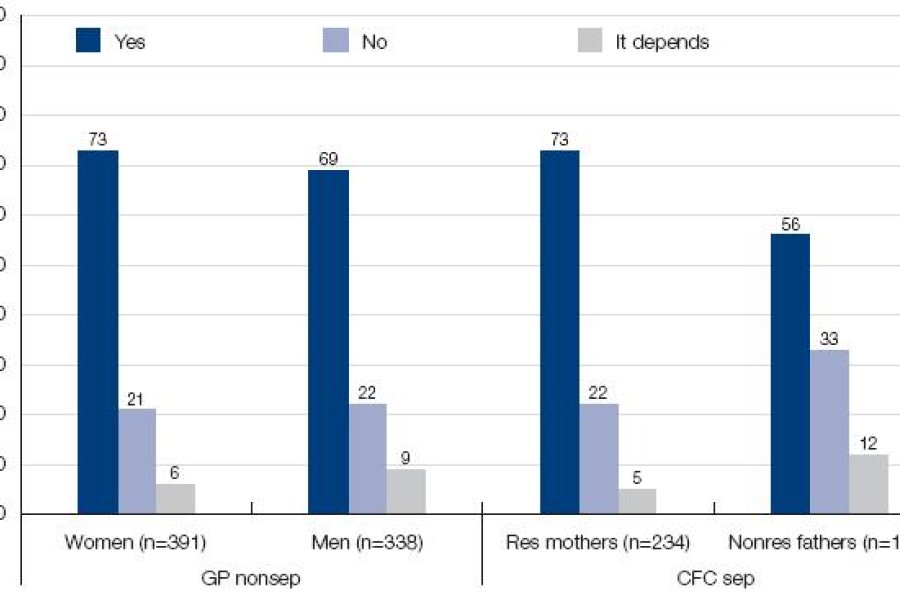

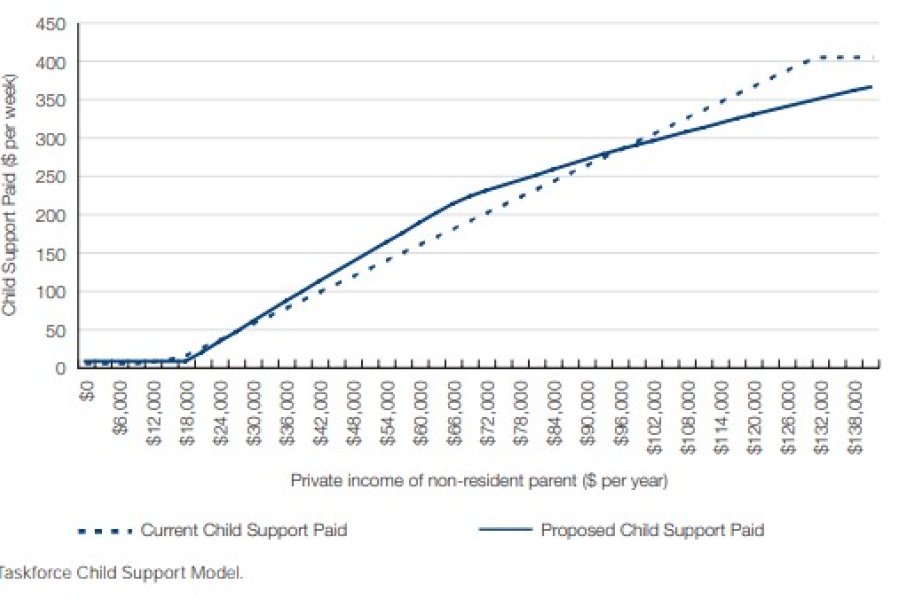

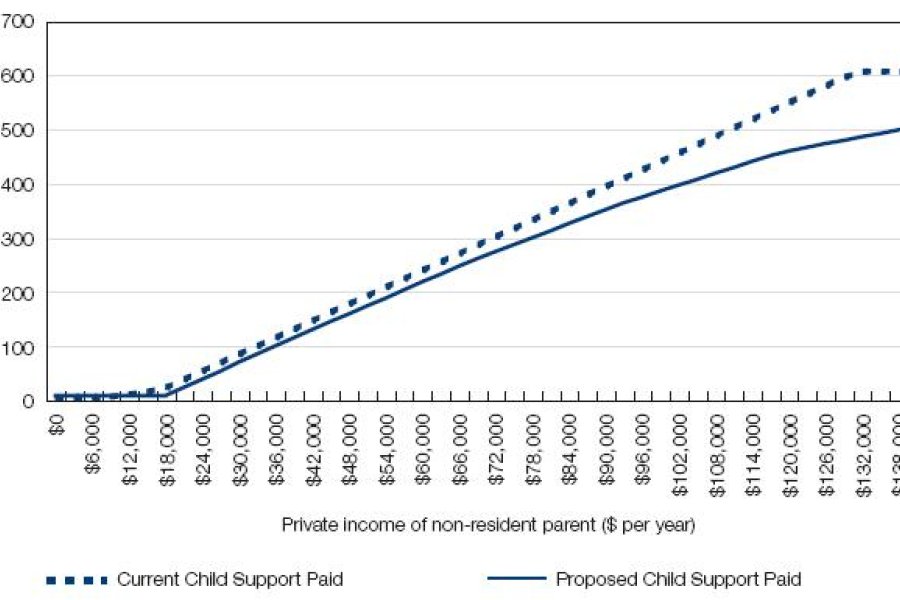

AIFS survey results in Figures 9.3 and 9.4 show broad community support for a minimum child support obligation.

Figure 9.3: Do you think a father who does not usually live with his children should pay some child support even if his earnings are very low or he only receives government income support?

Notes: GP nonsep = general population non-separated sub-sample; CFC sep = Caring for Children after Parental Separation sample comprising separated/divorced parents with at least one child under 18; χ2 (6) = 19.74, p<.01.

Smyth B. & Weston R., ‘A snapshot of contemporary attitudes to child support’, in Volume 2 of this Report, p. 29.

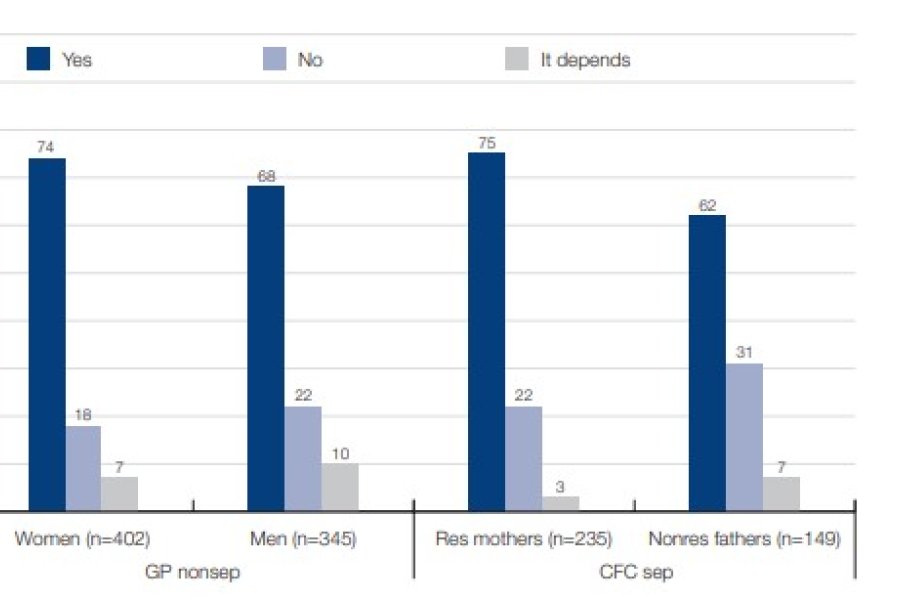

Figure 9.4: Do you think a mother who does not usually live with her children should pay some child support even if her earnings are very low or she only receives government income support?

Notes: GP nonsep = general population non-separated sub-sample; CFC sep = Caring for Children after Parental Separation sample comprising separated/divorced parents with at least one child under 18; χ2 (6) = 21.65, p<.01.

Smyth B. & Weston R., ‘A snapshot of contemporary attitudes to child support’, in Volume 2 of this Report, p. 29.

Most respondents in all groups thought that non-resident mothers and fathers on low incomes should, like all other non-resident parents, pay some child support. This view was advanced by close to 60% or more respondents in the four groups.

The Parliamentary Committee endorsed the earlier introduction of the minimum paymen, but commented that they felt the amount was now too low. It recommended an increase to $10 per week. This is one of the specific issues on which the Taskforce was asked to advise further in its Terms of Reference.

There was strong support within the Reference Group for an increased minimum rate, or at least applying a minimum rate per child, although there were also concerns that the minimum remain affordable to very low income parents, who may be receiving only income support payments. For this reason, some members of the Reference Group had reservations about the Parliamentary Committee’s recommendation that the sum be increased to $10 per week, since this represents a significant sum for those on Newstart Allowance.

Accordingly, the Taskforce, advised by the Reference Group, thinks it is more appropriate that the current minimum be increased by reference to the level of infl ation since 1999. Income support pensions and benefits are adjusted on different bases, with some linked to movements in average wages, and others to the movements in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The basic income support payment for a person seeking work has been linked to the CPI. The Taskforce therefore proposes that the minimum be indexed to changes in the CPI. This indexation should date from 1999, when the minimum payment was first introduced. This would require an increase, projected to the end of this calendar year, to about $6 per week.

Currently, where a payer is liable to support children with different carers, the $5 weekly minimum rate is divided between the carers in proportion to the number of children each cares for. It is hardly worthwhile to distribute such small amounts. The numbers of such cases is relatively small. The Reference Group advised that the minimum should be applied on a per case basis, and this recommendation was accepted by the Taskforce.

In keeping with the general principles of the income-shares approach, parents who are having regular contact with their child are contributing to the child by undertaking that care, and no payment should then be required. It can be assumed that these parents will be paying at least an equivalent to the minimum payment in caring for the child while having this regular contact. This is also the position where parents are sharing the care of the child.

Recommendation 1.24

All payers should pay at least a minimum rate equivalent to $5 per week per child support case, indexed to changes in the CPI since 1999. The increased amount should be rounded to the nearest 10 cents.

Recommendation 1.25

A minimum payment should not be required if the payer has regular contact or shared care.

Currently the system also permits a parent who has a significant reduction in income to notify the CSA, and have their assessment reduced to reflect their current income. Where the parent is in receipt of income support payments, the liability resulting will generally only be a minimum liability. Immediately the parent’s income situation has improved, they are required to notify the CSA, and their assessment is increased.

The Taskforce is aware that there are financial disincentives to improve workforce participation at income levels low enough that income support is payable. The Taskforce considers that it is sensible to allow parents a short period during which their child support obligations remain low, while they manage the costs of resuming employment. People starting a new job usually have to wait a while before their first pay day, depending on the pay cycle. The period of time after which the CSA needs to be notifi ed of the new income should not be too long, otherwise a disproportionate burden to support the children would fall on the other parent and the Government through family assistance. On balance, the Taskforce proposes a month beyond the usual time at which child support obligations would be increased.

Recommendation 1.26

Payers on the minimum rate should be allowed to remain on that rate for one month after ceasing to be on income support payments or otherwise increasing their income to a level that justifies a child support payment above the minimum rate.

Fixed payments

As reported in Chapter 6, more than 40% of all payers in the Child Support Scheme are paying $260 per year or less due to having low incomes. Only about half of these are on Newstart Allowance, Disability Pension, or other income support. It is likely that the reported taxable incomes of many of the remainder do not reflect their real capacity to pay a reasonable amount towards the support of their children.

The use of taxable income as the basis of child support means that those people who legally or illegally manage to minimise their tax also pay unrealistically low levels of child support. The House of Representatives Committee noted that for payers who are manipulating their taxable income to minimise or avoid taxation, there are many opportunities to also avoid paying child support. This is the case whether the manipulation is legal for the purposes of the tax laws or otherwise.

The CSA currently has powers to examine the taxable income of a parent on an individualised basis, and substitute an income that better represents that parent’s capacity. However, this is via the Registrar-initiated change of assessment process, and so is individualised, slow and involves significant administrative effort. There is a more generalised way of identifying parents whose taxable income may not fairly represent their true income, by reference to income support eligibility. Where a parent is genuinely on a low income, they are entitled to government support to meet basic needs. Parents who are apparently on a low income but not in receipt of government benefits are likely to have access to other income that they do not or need not declare as their taxable income.

The required child support payment should be $20 per week per child for those who were not on income support during the tax year on which the current child support liability is calculated, and who report taxable incomes below the level of maximum Parenting Payment (Single).

Parents may apply to the Child Support Registrar for a reduction where they wish to argue that they should not be subject to a fixed payment. The fixed payment may be reduced if the parent can demonstrate to the Registrar’s satisfaction that he or she truly has a level of total financial resources not exceeding basic pension level. Total fi nancial resources in this context include their access to income from any source to meet their living expenses, including from another person. If the parent chooses to live off the income of a new partner, but has a capacity to earn for himself or herself, then the $20 per week per child obligation, at least, should apply. This is consistent with the recommendation on capacity to earn in Chapter 12.

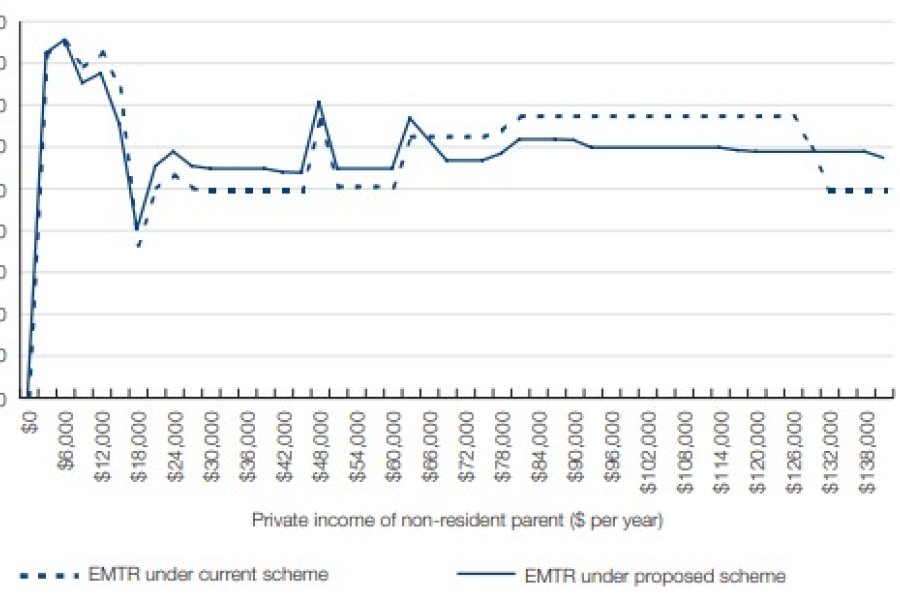

In order to satisfy the Registrar that the fixed payment will not apply, parents will need to approach the CSA and lay open their finances to scrutiny. This may also trigger scrutiny by the Australian Taxation Office. In some cases, there will be a ready explanation for the parent’s low income, despite not being on benefits, and once the explanation has been given and accepted, only a change in circumstances would result in any fresh inquiry or imposition of the fixed payment in future child support years. However, it would not be a sufficient explanation that the payer’s financial affairs are organised mainly through companies or trusts. What may be legal for tax purposes will not necessarily be a good enough reason to fail to make an adequate contribution to the support of one’s own children. This is consistent with the body of case law on capacity to pay, which allows the Senior Case Officers or the courts, on a change of assessment application, to go behind company and trust structures, and to impute an income if a person is likely to be engaging in cash transactions to avoid tax.