Wave 3.5 findings

In this section we highlight some of the findings from Wave 3.5, using unweighted data. Because some population groups were less likely to respond to the mail-out survey, and the mid-wave data are not weighted to account for this, the percentages may differ slightly from the estimated proportions in the Australian population.

For the B cohort, in about 95 per cent of cases the form was filled out by the child’s mother and 5 per cent were filled out by the child’s father. The corresponding figures for the K cohort were 93 per cent and 7 per cent. In both cohorts, an extremely small number of questionnaires were filled out by somebody else caring for the child.

Schooling

At the time of the mid-wave survey, 78 per cent of younger study children were in their first year at school (known as prep, kindergarten, reception) and around 18 per cent were in their second year at school (Year 1). The majority of parents (96 per cent) whose child attended school (defined as Grade 1 and kindergarten/prep/reception) reported their child looking forward to school every day or most days and only 2 per cent reported their child was upset going to school most days or every day. The majority of parents whose children attended school found their child’s transition to school easy (96 per cent), while a small number found it difficult (4 per cent).

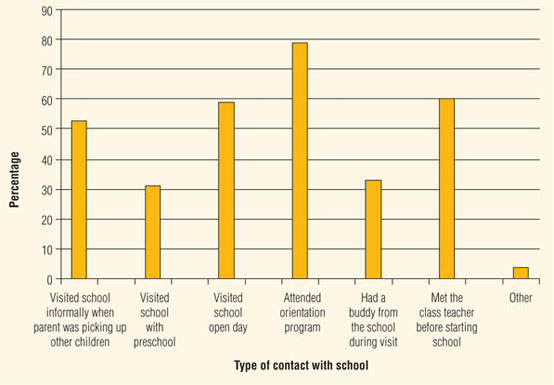

Starting school is a critically important time in children’s lives. This transition can be challenging for some children and can have significant impacts on the child’s ongoing learning. To better understand this transition, the Wave 3.5 questionnaire asked about support the B cohort study children who were attending school received before they first started (as shown in Figure 2). The majority attended orientation programs (79 per cent) at their schools before starting their first year, 60 per cent met their teacher and 59 per cent attended an open day at the school before starting. Most parents also received some form of introduction to the school such as attending orientation programs (81 per cent), receiving mail-out information (81 per cent) or meeting with the principal or the class teacher (78 per cent). Figure 2 shows the type of introduction B cohort families received prior to the study child starting school.

Figure 2: B cohort child's contact with school before starting full-time

Source: LSAC B cohort, Wave 3.5 data.

Parents of both cohorts reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the quality of education their child received (B=98 per cent; K=94 per cent). Parents of the older cohort said they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the study child’s progress with maths (91 per cent), reading (93 per cent) and their overall progress (94 per cent). Just over half the K cohort parents (52 per cent) said they believed their child’s overall achievement to be above average and 48 per cent rated their child’s achievement as average or below.

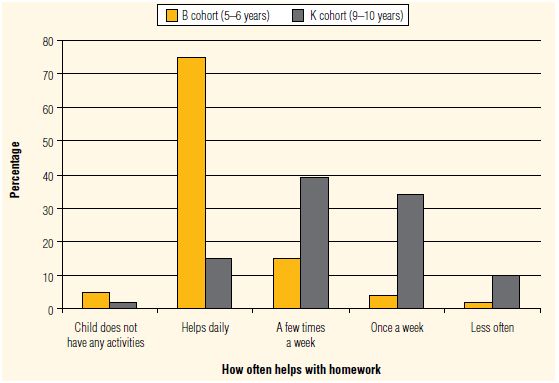

Three-quarters (75 per cent) of the B cohort parents helped the study child daily with homework tasks set by their teacher while only 15 per cent of parents of K cohort study children reported doing this (Figure 3). The difference between the B and K cohorts is likely to reflect how the older cohort is increasingly able to engage with homework activities with less direction from their parents. It also may be due to the emphasis placed on parents listening to their children read every night during the early years of school.

Figure 3: How often parents help the study child with their homewok

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

Parents overwhelmingly reported positive relationships between: the study child and their teacher (B=99 per cent, K=99 per cent), themselves and the child’s teacher (B=98 per cent, K=97 per cent), and themselves and the child’s school (B=99 per cent, K=99 per cent). These numbers paint a positive picture of the interactions between study families and their child’s school.

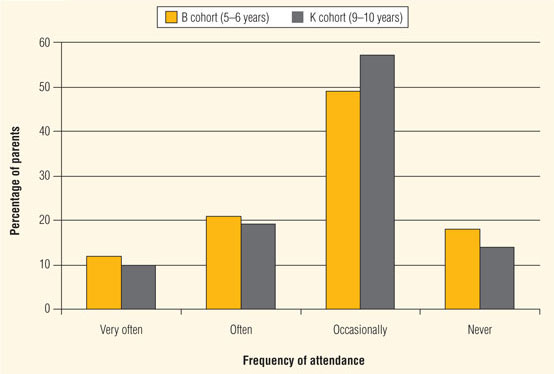

While parents report satisfaction with their relationships with the child’s school, it is interesting that 33 per cent of parents of the B cohort attended parent-teacher meetings very often or often, 49 per cent did occasionally and 18 per cent never attended parent-teacher meetings (see Figure 4). Nearly 30 per cent of parents from the K cohort attended parent-teacher meetings very often or often while 57 per cent did occasionally and 14 per cent never attended them. There are many possible explanations for these responses. Many schools may only hold parent-teacher meetings once or twice a year, which parents would be likely to report as occasionally. Some parents may rely on their partner to attend these events or may see no reason to attend if their child is doing well. There is probably also a subset of parents who chose not to engage with the school.

Figure 4: How often parents attend parent-teacher meetings

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

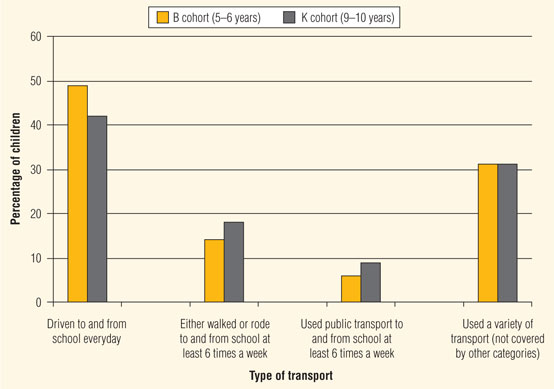

The Wave 3.5 questionnaire also asked parents how their children travelled to and from school. By looking at the different types of transport children use, we can gain an insight into some of the regular incidental physical activities children are involved in, about the impact on parents who accompany their children to school, and how this changes as children take on more personal responsibility. We can also look at how distance from school impacts on the method of transport used.

Parents of both cohorts were asked what type of transport their child used for (a) going to school and (b) coming home from school, for each day of the week. Only very small numbers of children used a type of transport involving physical activity or public transport to and from school every day of the week. To get an understanding of the number of children undertaking at least some physical activity in their trip to school, a new variable was created showing children who walked, bicycled or used a scooter to go to school on at least six trips (either to or from school) per week. A similar variable was created for children who used public transport on at least six trips (either to or from school) per week. The percentage of children in these two categories, those who were driven to school every day, and children who used a variety of different transport types is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Comparison of the types of transport used to get to and from school by cohort

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

While children are mostly driven to and from school everyday (B cohort=49 per cent; K cohort=42 per cent), 18 per cent of K cohort children and 14 per cent of B cohort children rode or walked on at least six trips (to or from school) per week. Only 9 per cent of the K cohort and 6 per cent of B cohort children used public transport on at least six trips per week. The remaining study children used a mixture of modes of transport to get to and from school not covered by these other categories (31 per cent of B and K cohort children).

The type of transport used to get to and from school could be influenced by a range of factors including the distance from home to school, the other responsibilities of the child’s parents (especially work), the safety of the neighbourhood and the maturity of the child. For example, as might be expected, Figure 5 shows that the older K cohort children are more likely to take other forms of transport than have their parents drive them to and from school.

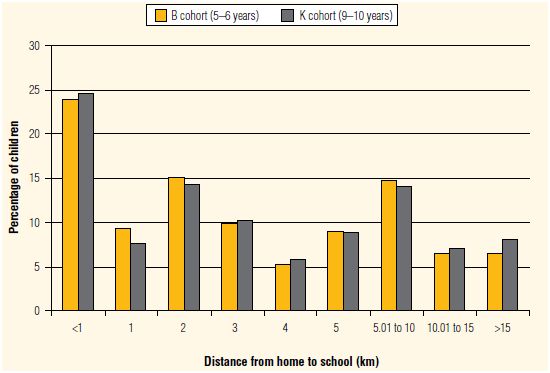

The majority of parents across the two cohorts reported living five kilometres or less from the study child’s school. Figure 6 shows the distribution of distances the B cohort and K cohort children live from their school. As illustrated below, the two cohorts show a very similar distribution. Fifty-eight per cent of B cohort children and 56 per cent of the K cohort children live within three kilometres of their school. Around 71 per cent of both B and K cohort children live within five kilometres of their school.

Figure 6: Reported distance from school to home by B and K cohort children

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

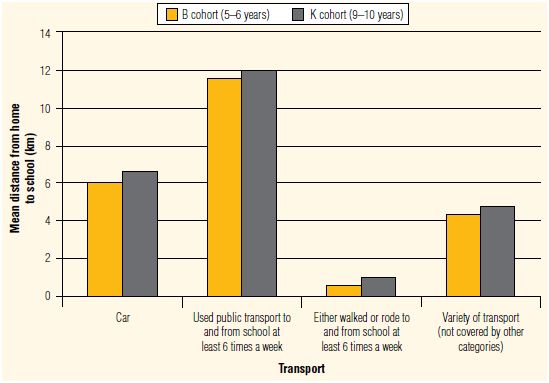

Figure 7 plots the mean distance between home and school by the type of transport taken and cohort. For families where the study child is driven to and from school every day, families lived an average of 6 and 6.5 kilometres from school for the B and K cohort children respectively. Children who use public transport on six or more trips week, live on average 11.5 kilometres (B cohort) and 12 kilometres (K cohort) from school. Those who ride or walk at least six times a week live much closer to school, at an average of 0.6 kilometre (B) and 1 kilometre (K).

Figure 7: Mean distance between school and home by mode of transport and cohort

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

Health

The health section of the Wave 3.5 explored parents’ overall perception of their child’s health, sleep patterns and pubertal development for the older group. Over 90 per cent of parents in each cohort thought their child’s health was good, very good or excellent.

Parents were also asked about the study child’s sleeping patterns, on both school days and non-school days.

Child development experts recommend that children aged 5 to 12 years should get about 10 to 11 hours sleep per night.2

On average, the B cohort children slept 10 hours and 49 minutes on a school night and 10 hours and 41 minutes on a non-school night. The K cohort children slept, on average, 10 hours and 12 minutes on a school night and 10 hours and 5 minutes on a non-school night. On average children in both cohorts do get the amount of sleep recommended by experts.

However, some children do fall outside the recommended amount of sleep they should be getting. Twelve per cent of the B cohort children slept less than 10 hours and 24 per cent slept more than 11 hours on a non-school night. On a school night, 6 per cent of B cohort children received less than 10 hours sleep, while 33 per cent had more than 11 hours of sleep.

On a school night, 57 per cent of B cohort children were reported to be in bed by 7:30pm, with 99 per cent in bed by 9pm. On non-school nights, 51 per cent of B cohort children were in bed by 8pm and 99 per cent were in bed by 10pm.

A higher number of children in the K cohort received less than the recommended amount of sleep when compared to the B cohort. On a school night, 24 per cent of K cohort children received less than 10 hours of sleep while only 5 per cent received over 11 hours. On a non-school night, 36 per cent of K cohort children received less than 10 hours and 7 per cent received over 11 hours.

On a school night, 44 per cent of K cohort parents reported their children went to bed by 8pm while 99 per cent of parents stated their child was in bed by 10pm. On a non-school night, 59 per cent of K cohort children were in bed by 9pm, increasing to 98 per cent by 10:30pm.

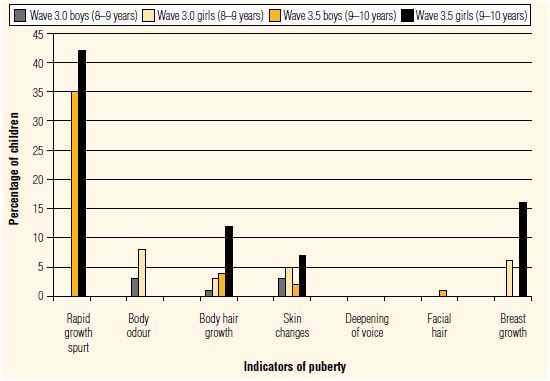

Wave 3 saw the introduction of questions about the onset of puberty for the K cohort. Four questions were asked in Wave 3 increasing to seven in Wave 3.5. Previous research shows that the first stages of puberty in girls can become evident from the age of 8 years continuing until 16 years of age, while in boys puberty starts anywhere between 10 to 12 years and can continue until 18 years of age.3

The study children at Wave 3.5 were 9 to 10 years of age and therefore we expected that some children would begin to show signs of puberty. Figure 8 shows the percentage of K cohort children showing signs of puberty, who participated in both Wave 3 and Wave 3.5, as reported by the main parent.

Figure 8: Parent report of puberty signs by sex of study child in Wave 3 and 3.5

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 3 & Wave 3.5.

Notes: Only those who completed both Wave 3 and Wave 3.5 included.

Skin changes, presence of body hair, and breast development were asked in both Wave 3 and 3.5, where as body odour was only measured in Wave 3. Deepening of the voice, rapid growth spurt and facial hair were only measured in Wave 3.5. Onset of menstruation was asked in Wave 3.5 but omitted due to unreliable data.

Figure 8 shows that the most common signs of puberty in the K cohort are rapid height increase (42 per cent of girls and 35 per cent of boys), followed by breast growth in girls (16 per cent), the appearance of body hair (12 per cent of girls and 4 per cent of boys) and skin changes (7 per cent of girls and 2 per cent of boys). Only 1 per cent of boys had started to experience facial hair growth while voice deepening does not appear to have started at this stage. The observed difference between the sexes is in line with the literature indicating that girls tend to start puberty younger than boys do.4

Media and technology

Parents of both cohorts reported they had rules surrounding their child’s use of media and technology in terms of both how much they use and what they watch. The vast majority of parents from both cohorts said they had rules about what programs the study child was allowed to watch on television (B=96 per cent; K=96 per cent). Just over three-quarters of both parent groups also reported they had rules on the amount of television children watched (B=77 per cent; K=76 per cent).

In July 2009, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) released a paper using LSAC Wave 2.5 data: Use of electronic media and communications: early childhood to teenage years—findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (3 to 4 and 7 to 8 years), and media and communications in Australian families (8 to 17 year olds), 2007. The study found that ‘rules regarding both television content and timing were more often in place for younger children, and declined with age’ (p. 13).

In Wave 3.5, both cohorts had rules on what they could do on the computer (B=94 per cent and K=94 per cent) while 3 per cent of both B and K cohort children did not have any rules and a further 3 per cent of B and K cohort parents reported that the question did not apply to their family. Parents reporting that rules on computer use did not apply could indicate these households do not have access to a computer.

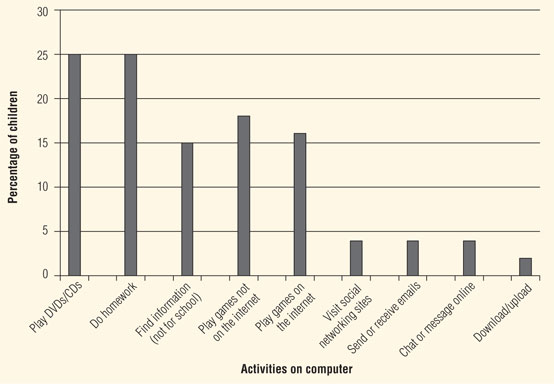

In Wave 3.5, 96 per cent of K cohort children had a computer at home and parents of these children were asked questions about their child’s use of the computer. Figure 9 shows what activities K cohort study children with access to a computer do on the computer at least once a week. Fifty-nine per cent of the K cohort children used it at least once a week to do their homework, 46 per cent played DVDs, 44 per cent used the computer to find information that was not related to school and 44 per cent used the computer to play games (that were not on the internet) at least once a week. Thirty-three per cent of K cohort children played games on the internet at least once a week, 30 per cent used the computer to send or receive emails, 11 per cent visited social networking websites, 9 per cent used the computer to chat or message online and 8 per cent used it to download or upload at least once a week.

Figure 9: The percentage of K cohort children (with access to a computer) and the type of activities they use it for at least once a week

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 3.5 data.

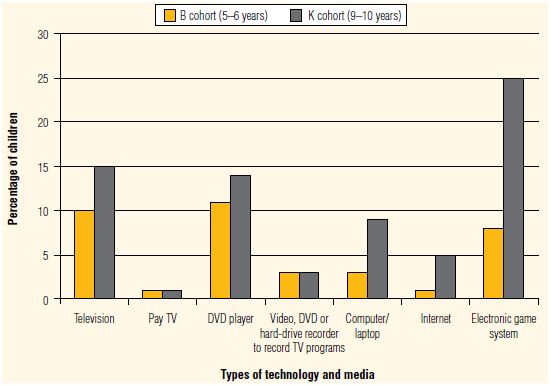

Parents also reported what types of media or technology their children had in their rooms. About 10 per cent of the B cohort and 15 per cent of the K cohort children had televisions in their rooms while fewer than 15 per cent of each group had a DVD player (B cohort=11 per cent; K cohort=14 per cent) in their rooms. This is interesting given that most experts recommend keeping television out of children’s bedrooms (see: <www.youngmedia.org.au(link is external)(Opens in a new tab/window)> and <www.raisingchildren.net.au(link is external)(Opens in a new tab/window)>). Figure 10 illustrates these findings.

Figure 10: Type of technology in study child's bedroom by percentage of children

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

The ACMA study reported similar findings on media technology in children’s bedrooms using Wave 2.5 of LSAC. They found children were more likely to have a television in their room than computer or internet access. They also found that older children were more likely to have a television, computer and/or internet access.5

In Wave 3.5, the largest difference between the B and K cohorts appeared with electronic games machines (such as Playstation, Xbox, Nintendo and handheld games devices). About one-quarter of K cohort children had access to gaming machines in their rooms compared to 8 per cent of the younger group.

Mobile phones are another form of media and technology children are increasingly using, with about one in 10 parents in the K cohort reporting that their child had a mobile phone for their own use. Of the 10 per cent of children who had a mobile phone for their own use, only 15 per cent of them used their phones to call friends one or more times a week while 30 per cent of them used their phones to text friends one or more times a week.

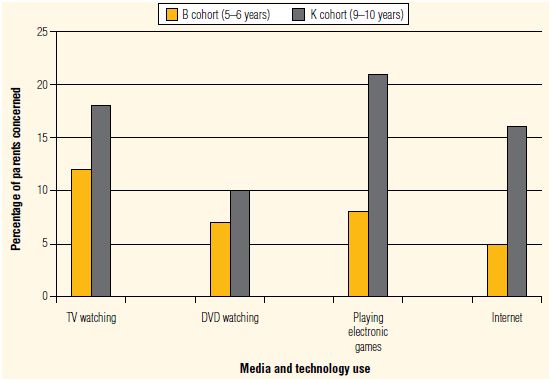

Study children are increasingly exposed to different forms of media and technology and the study asked parents about their concerns with what their children were doing and watching. Only a relatively small proportion of parents had concerns regarding their child’s use of media and technology, including TV and DVD watching, playing electronic games and using the internet (Figure 11). K cohort parents had higher levels of concern about their child’s media use compared to the B cohort. K cohort parents were most concerned about their child playing electronic games (21 per cent), followed by their TV watching (18 per cent), internet use (16 per cent), and DVD watching (10 per cent). By contrast, B cohort parents were most concerned about their child’s TV watching (12 per cent), followed by their electronic game use (8 per cent), DVD watching (7 per cent) and internet use (5 per cent).

Figure 11: Percentage of parents in B and K cohorts reporting concerns regarding media and technology use

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Wave 3.5 data.

- Sigelman, CK & Rider, AE 2008, Life-span human development, 6th edition, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, Belmont.

- Stedman, TL 2000, Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, 27th edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore.

- Stedman, TL 2000, Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, 27th edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore.

- Australian Communications and Media Authority 2009, Use of electronic media and communications: early childhood to teenage years—findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (3 to 4 and 7 to 8 years), and media and communications in Australian families (8 to 17 year olds), 2007, Australian Media and Communications Authority, Canberra, p. 6.